|

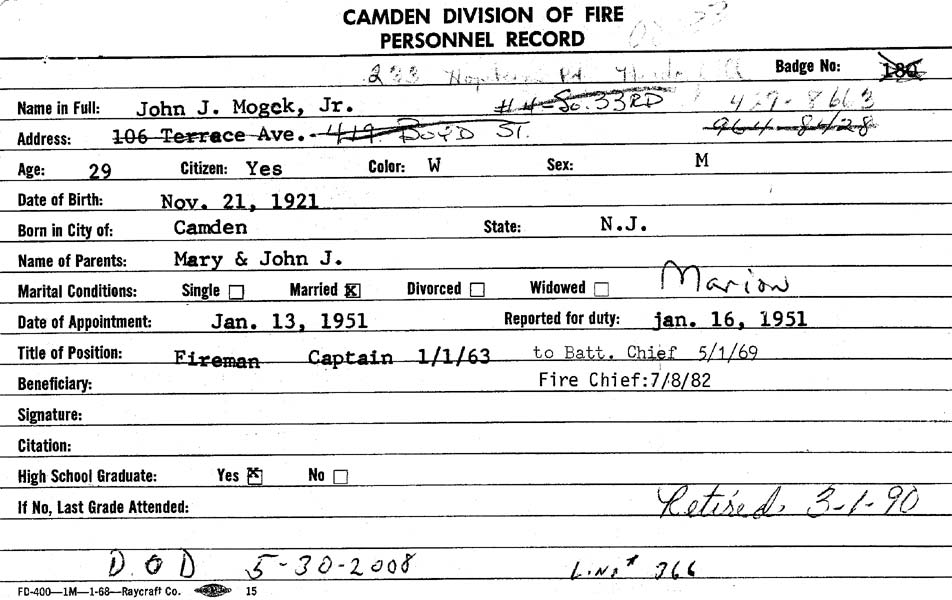

children. The first was a

daughter, Eleanor, then John Mogck Jr., and by 1930 there were

three more children, Thomas Edward, and Marie. At least one more

child, Betty, was born during the 1930s.

John

Mogck Jr. attended school at the

Holy

Name Roman Catholic Church school and graduated from

Camden

Catholic High School. He had attended St. Francis

College in

Loretto,

Pennsylvania

when called to arms after the Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor.

On

April 3rd, 1942 units of the Camden Fire Department's First

Battalion were responding to an alarm

at point

and Erie

Streets, North

Camden.

A group of children were on their way to a birthday party for

nine-year-old, Betty Mogck. The group of excited birthday

celebrants, hearing the fire engines coming, ran into the street

to see where they were going. As

Engine Company 2

was

making the

turn at Erie Street, the Chauffeur, Fireman

Harry

Kleinfelder

pulled hard on the wheel to avoid running over the children but

not before striking little Betty Mogck. The apparatus swerved to

the side of the street, sheared off a utility pole and came to

rest on the pavement. Two members were hurled to the ground,

slightly injured. Betty's older brother, John, was down the

block talking with friends and came running up the street. Betty

Mogck was rushed to Cooper

Hospital suffering from a broken leg.

Firemen William

Hopkins and

Harry Haines

were

treated for

bruises and released. Years later, Betty's brother,

John J.

Mogck, Jr. would himself enter the Department and rise from

the

ranks of Probationary Fireman to retire as Chief of

Department.

John

J. Mogck Jr. was assigned to the

115th

AAA Gun Battalion (mobile). This unit organized at Camp

Davis,

North

Carolina in March of 1943, and left for England via New York in

December

of that year. The 115th participated in the Battle of Britain

(anti-aircraft defense of London), the landings at Normandy at

Omaha

Beach in June 1944 and fought its way across France and into

Germany

with Patton's Third Army. The battalion was present at the Third

Army's

crossing of the Rhine in 1945, and finished the war at

Abensberg,

Germany. John Mogck Jr. had been promoted to Technical Sergeant

and had

been awarded the Bronze Star by the time he was discharged from

the

Army.

After

the war John J. Mogck Jr. returned to Camden and the family home

at 40

Wood

Street. The 1947 City Directory lists his occupation as

student,

indicating that he had returned to college. At 50

Wood

Street, a neighbor, Ervin Brennan, had joined the Camden

Fire

Department. Interestingly enough, of the 20 houses standing on

Wood

Street in 1947, at least four had family members or

relatives who either had been, were in, or would be members of

the Camden Fire Department, the other two men being Philip

Bocelli and Joseph J. Randik Jr.

John

J. Mogck Jr. joined the Camden Fire

department on January 13, 1951. Early in his career he was

assigned to

Ladder Company

1,

based at Fire Headquarters at

North

5th

Street

and Arch

Street. He also was detailed for service in other

capacities.

|

|

Firefighter

John J. Mogck Jr.

Ladder

Company No. 1

Circa

1954

|

Between

1950 and 1959 the Fire Department replaced its entire fleet of

hose wagons. The Fire Department's vehicle maintenance was done

at Camden's municipal garage

under the direction of superintendent Al Healy, Assistant

Joe

Snyder and Fire Mechanics Earl VanSandt and Ed Campbell

would

design and manufacture most of these apparatus in-hose. Fireman

John J. Mogck

Jr.,

who was by the time he joined the Fire

Department well trained in the use of welding and cutting, would

be detailed to the shop as needed. The Department would acquire

commercial truck chassis upon which the hose wagon bodies would

be fabricated. The first of these units was a 1951 GMC 2-1/2 ton

cab and chassis. The hose wagon body was equipped with a 250

gallon per minute hale pump, a 1000 gallon per minute deckpipe,

a 150 gallon booster tank, and a cartridge canister containing

"Wet Water"- an additive agent designed to allow water

to penetrate and soak through deep seated fire in baled rags,

paper, and similar materials. Engine Company and 8 and Engine

Company 2 were the first to receive the new hose wagons. In

later years Dodge cab and chassis trucks were utilized.

|

|

|

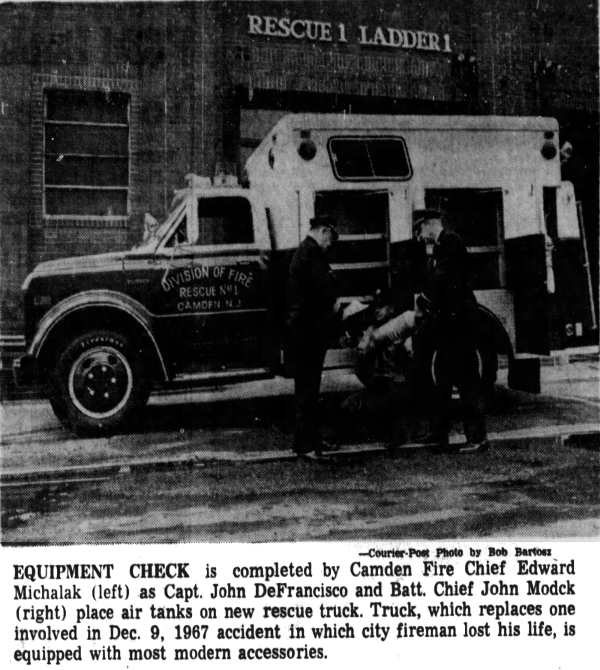

July

18, 1960- An industrial accident with a fatality, at

the

Cooper River at

Baird

Avenue. A Front end loader flipped

off embankment pinning the operator

underwater.

In

the foreground without shirt: Battalion Chief

William

Deitz, 2nd Battalion, who first

arrived

at

scene and attempted rescue of operator. Members

of

Rescue Company 1 are Fireman

Edward Brendlinger

(kneeling on the machine's wheel) and Firemen

John

Mogck Jr. and

James McGrory in the boat.

Battalion Chief Deitz would later be killed in

the line

of duty and Fireman

John

Mogck would become Chief of

Department.

|

Fireman

Mogck's abilities outside the maintenance shop were recognized,

and on January 1, 1963 he was promoted to Captain. On May 1,

1969 he was appointed Battalion Chief.

In

the spring of 1981, following three year tenure as Chief of

Department,

Theodore L. Primas retired after nearly thirty-five years of

service in

the Uniformed Force.

Chief

John J. Mogck Jr. was appointed as his successor. Like

his

predecessor, Theodore

Primas, the Fire

Administration that

Chief

Mogck would inherit was fraught with fiscal constraint

while the

demand for fire services continued to reach all time highs.

Chief Mogck

was sworn in on July 8, 1982. O that same day at 1800 hours

Engine Company 3 left its building at 1815 Broadway, whichhad

become unsafe, and moved in with Engine Company 10 on Morgan

Boulevard.

As

Chief John J.

Mogck

Jr. assumed the helm of the Department, the City faced

yet

another

fiscal crisis amid looming budget deficits. An ever decreasing

tax base

coupled with recurring shortfalls-in revenue, created the worst

possible

conditions. The City's ability to increase revenues was thwarted

by an

ever shrinking source of ratables. While thousands of vacant

buildings

bled city coffers of critically needed revenue, infusions of

State and

Federal aid already in place could not close the budget gap. As

municipal services were curtailed throughout every city agency,

the Fire

Department became no exception. On April 13th just two weeks

after his

appointment Chief

Mogck was compelled to order the disbanding of

Engine Company

2.

Following 112 years of service to center city,

Engine Company

2 passed

into history.

For

1981 the Department sustained a record high of 38 Greater Alarms

for the

year. The loss of Engine Company 2 only exacerbated an already

overburdened Fire Control Force. With its retrenchment to just

eight

engine companies, the Department's dependency upon mutual aid

services

continued to expand dramatically. While other urban fire

departments in

the State of New Jersey of comparable size to Camden, incurred

only a

few incidents of mutual aid in the course of a year, it was not

uncommon

for Camden to summon mutual aid services on as many as fifty and

sixty

occasions within any twelve month period.

Under

the auspice of a regional Fire Communications Center, mutual aid

services throughout Camden County had been greatly improved,

both in

terms of coverage and unit deployment. For over a hundred years,

the

mutual aid policy in the City of Camden involved a cumbersome

and

inefficient method, whereby mutual aid services could only be

summoned

upon the expressed order of the Chief of Department. The

Department's

resource base allocated to a fourth alarm level under the

classification

of General Alarm would only summon scheduled mutual aid when

that

incident level was reached.

This

policy remained seriously flawed and created interim gaps in the

continuity of fire protection. In the event of simultaneous

incidents,

where many resources were committed in a short period of time

leaving

large sections of the City devoid of available fire companies,

the

dispatcher was first required to contact the Chief of Department

or his

designee, to authorize mutual aid response. While this process

of

contact and solicited authorization could take more than just a

few

moments, the assignment and response of mutual aid units were

often

delayed. The Department would alleviate this long standing

deficiency by

implementing a policy of automatic mutual aid in conjunction

with other

refinements.

The

Supervising Fire Dispatcher was charged with the responsibility

for

ensuring that the City never fell below a specified level of

available

resources. Partial mutual aid coverage would be automatically

summoned

to maintain this minimum balance at all times. Upon reaching a

fourth

alarm level or the equivalent thereof, full mutual aid services

would be

automatically enacted. Also the long standing classification of

General

Alarm was discarded, as response policies were expanded to a

ninth alarm

level to include the automatic deployment of mutual aid units.

These

refinements substantially enhanced the quality of fire services

in the

City, and also made optimum use of the Department's regional

communications capability.

One

of the first major incidents to occur under the new mutual aid

policy

was a spectacular seventh alarm for the H & M pallet factory

at

Walnut

and Pine

Streets, South Camden. Shortly after 9 P.M., on July 13,

1981, first alarm nits found a well advanced fire in a large

outside

yard spreading through hundreds of piles of stacked wooden

pallets.

Tremendous fire conditions ignited thousands of tinder dry,

industrial

size pallets, as Greater Alarms were transmitted in rapid

succession.

Buildings occupied by the National Heating Company on Magnolia

Avenue

became seriously exposed as blazing fire brands ignited the

roofs of

other nearby properties. A densely populated residential

neighborhood

immediately adjoining the fire was evacuated by Police as fire

storm

conditions whipped cyclonic columns of flame hundreds of feet

into the

sky. Chief

Mogck

transmitted sixth and seventh alarms with orders for incoming

companies

to take hydrants on Haddon Avenue and stretch into the fire from

over

five blocks away. Numerous master streams employed along the

perimeter

of the blaze, barely reduced the blistering temperatures. At the

height

of the fire, the manpower of two engine companies advanced a

deckpipe up

a driveway to cover a seriously exposed fuel tank while a third

company

manning a big handline, drenched the crews to protect them from

withering heat.

On

March 8, 1981, shortly before noon, the Box was transmitted for

Mt.

Ephraim Avenue and Olympia Road in the Fairview section of South

Camden.

As the responding companies were underway, the dispatcher began

receiving numerous calls for a fire at the Gaudio Brothers

Garden Supply

Center. The 3rd Battalion ordered a second alarm on arrival as

heavy

fire raced across the ceiling of the one-story, block long

building. A

looming column of black smoke was visible for miles as the fire

building, without exposures, was destroyed in this third

alarm.

Among

numerous other second alarms, another third alarm on April 20,

1981,

destroyed a vacant commercial building near

Fourth

and

Mt.

Vernon

Streets, South Camden. On July 6th shortly after 5:30

P.M.,

units of the

3rd Battalion turned out for

Broadway

and

Jackson

Street. Four alarms

for another spectacular lumber yard fire kept units heavily

engaged for

hours. During the windy afternoon of November 2nd, three alarms

for a

pallet factory at Eighth and

Bailey

Streets, North

Camden, challenged

fire fighters as extreme radiant heat threatened nearby

dwellings. The

placement of master streams checked this potential

conflagration.

The

month of August 1981 was especially busy for

East Camden fire

fighters.

Units of the 2nd Battalion attended several second alarms in the

East Camden

section. Shortly after midnight on August 4th, a telephone alarm

was received for a vacant factory near 17th and

Federal

Streets. Three

alarms were transmitted for this Box as fire fighters fought to

get the

upper hand on a stubborn blaze in a vacant block long commercial

building. On August 29th near 9 P.M., units again responded to

17th and

Federal

Streets for a fire in a lumber yard. A fifth alarm plus

numerous

special calls were transmitted for this incident as more than

200 fire

fighters battled tremendous fire conditions for several

hours.

During

1982 the Department responded to a record high of nearly eleven

thousand

alarms, thirty-seven of which were Greater Alarm incidents. Of

these,

the most notable incident involved yet another spectacular blaze

in a

complex of mill buildings in the

Cramer Hill

section.

On

the evening of June 30th, a full assignment of units were

dispatched on

a phone alarm to

State

Street and River Avenue for a reported dwelling

fire in the Ablett

Village Housing Projects. Upon arrival units found

nothing, and conducted an investigation of the neighborhood

before

declaring the incident a false alarm. There was no evidence of

smoke or

fire anywhere in the area. Just twenty minutes later the Box for

State

and River was again transmitted, now reporting a factory.

Within

ten minutes of his arrival,

Chief

Mogck ordered simultaneous sixth and seventh alarms,

followed a

few

minutes later by the eighth alarm. Companies coming in on

Greater Alarms

were ordered to take hydrants many blocks away from the fire and

piece

each other out in pumper to pumper relays. Numerous master

streams and

ladderpipes were brought to bear on the blaze as the fire storm

generated ground winds estimated at 30 MPH. At the height of the

fire,

as many as ten separate buildings in the Pon Pas complex were

fully

involved, several of which individually, would have been third

or fourth

alarm incidents in themselves.

As

Engine Company

11

entered River Avenue from

27th

Street, the members

couldn't believe their eyes. The officer grabbed the radio

handset and

reported that he was still twelve blocks out and had heavy fire

showing

in the sky. Among so many memorable fires throughout the years,

this

incident would join the list as certainly one of the most

spectacular in

the long history of the Department. The former site of the

Bartol Tire

Company comprised a complex of two, three, and four-story loft

buildings, all of mill type construction. At the time of the

fire, the

complex was occupied by the infamous Pon Pas Waste Paper

Company, a long

established firm with a history of major fires throughout the

City of

Camden. The buildings in the complex were loaded from floor to

ceiling

with huge bales of waste paper. The corner structure at State

Street and

River Avenue was a three-story loft measuring 100 x 400. As

Chief James

Smith, 2nd Battalion, left the firehouse nearly a mile away, he

could

see massive flames illuminating the distant horizon.

Upon

arrival at the scene,

Engine

Company 11 was met with blow torch

conditions as fire involved the entire length and height of the

corner

loft. As Ladder

Company

3 came down the hill on East State Street

approaching River Avenue, they could see fire venting from more

than

fifty windows. Tremendous radiant heat conditions made the

intersection

untenable as Engine

Company 11 attempted to get its deckpipe in service

at the corner of the building. Third, fourth and fifth alarms

were

pulled within five minutes of the initial alarm. No one could

understand

how such a catastrophic volume of fire could develop in such a

short

period of time. Fire fighters had answered the false alarm near

this

intersection just twenty minutes earlier.

Within

the first thirty minutes, the fire extended to involve no less

than five

interconnected buildings.

Chief

Mogck responding on the third alarm arrived within

twenty

minutes to

find fire storm conditions, as tons of burning paper stock

fueled the

ferocious blaze. Upon arrival,

Chief

Mogck ordered an immediate evacuation of numerous

dwellings in

the

Ablett Village Housing Project. On the

East

State

Street side of the

fire separated by just the thirty foot width of the street,

stood a

massive complex of one-story commercial buildings, some which

measured

500 x 1000 in size. These properties, the former site of an RCA

warehouse facility, were severely exposed by radiant heat and a

tremendous flying ember problem. Located downwind of the fire

approximately one-half mile, were the Conrail freight yards, one

of the

largest rail facilities on the east coast. Hundreds of tank

cars, box

cars and other rolling stock were seriously exposed by large

burning

fire brands that billowed skyward and were carried toward East

Camden in

a huge thermal column.

Within

ten minutes of his arrival,

Chief

Mogck ordered simultaneous sixth and seventh alarms,

followed a

few

minutes later by the eighth alarm. Companies coming in on

Greater Alarms

were ordered to take hydrants many blocks away from the fire and

piece

each other out in pumper to pumper relays. Numerous master

streams and

ladderpipes were brought to bear on the blaze as the fire storm

generated ground winds estimated at 30 MPH. At the height of the

fire,

as many as ten separate buildings in the Pon Pas complex were

fully

involved, several of which individually, would have been third

or fourth

alarm incidents in themselves.

As

the fire communicated across

East

State

Street

to involve a large one

story commercial building in the former RCA complex, the ninth

alarm was

transmitted with units assigned to cover this critical exposure.

In the

interim, several engine companies were special called to the

vicinity of

East

State

and

Federal

Streets nearly a half mile away, to perform brand

patrol in residential neighborhoods of

East Camden, where

embers

were

reported on the roofs of many frame dwellings. At least two more

engine

companies above the ninth alarm were also special called to the

Conrail

Yards downwind of the fire, to extinguish and monitor flying

brands in

that sector. Fire storm conditions existed for more than three

hours

until numerous structural collapses and dozens of master streams

began

to abate the flames. Overhauling hundreds of tons of waste baled

paper

would last for nearly a week. In a large yard at the center of

the

complex, a dozen forty foot box trailers, also loaded with baled

waste

paper were incinerated and contributed to the massive cleanup of

ruins.

Some forty fire companies had to be used to control this

incident.

On

February 10, 1982, about 2 A.M. a smoky fourth alarm heavily

damaged

several offices on the fourteenth floor of the City Hall

tower.

Between

March and May the Department would attend at least a dozen

second

alarms. A third alarm on March 12th burned out one apartment on

the

ninth floor of Northgate II, a twenty-story apartment building

at

Seventh

and

Linden Streets, North

Camden. On June 21st, a tough third

alarm in an occupied warehouse near 11th Street and

Ferry

Avenue, South

Camden, taxed the endurance of fire fighters under conditions of

heavy

smoke and hot, humid weather. The summer months of July, August

and

September also remained very active among a dozen other Greater

Alarms

and many working fires.

On

October 6, 1982, a few minutes after 6 P.M., the Box was

transmitted for

Seventh

and

Pine

Streets, South Camden, reporting a fire in a commercial

building. Engine

Company

8 arriving first due, found a vacant one-story

warehouse, 150 x 300 with fire venting through the roof. Four

alarms

were pulled in quick succession to prevent the blaze from

extending to

numerous occupied row dwellings that adjoined the fire building.

On

November 9th, yet another third alarm gutted a fourth floor

apartment in

the Northgate II high rise at

Seventh

and

Linden Streets, North

Camden.

Just two weeks before, a smoky late night blaze occurred in an

underground parking garage at the Northgate I Tower, on the

opposite

side of

Seventh

Street.

A

very active year for Greater Alarms would close on December 27th

with a

third alarm involving a row of vacant dwellings at Ninth and

State

Streets, North

Camden. This midnight blaze routed several families from

nearby homes, into the cold darkness as fire fighters worked to

contain

the involvement of four buildings.

A

MATTER OF RISK MANAGEMENT

Among

nearly eleven thousand alarms during 1982, the Department also

sustained

a record high of more than 6,000 malicious false alarms for a

single

year. In some regions of the City, it was not uncommon for an

engine

company to answer as many as ten and twelve false alarms at the

same

pulled box in a single day. An epidemic of malicious false

alarms from

street boxes were stripping many areas of the City of essential

fire

protection as companies responded from one false alarm to the

next. This

burden, coupled with an increasing number of working fires posed

serious

risk to fire fighters and public alike. The Fire Administration

was

compelled to re-evaluate its mission and develop effective

solutions to

combat this ever growing problem.

Initial

considerations focused upon the total elimination of the

municipal fire

alarm system. This solution would transfer all public reporting

of fire

incidents to the domestic telephone system. Among a number of

cited

concerns, the availability of telephone service - both public

and

residential throughout many areas of the City remained highly

problematic. Public telephones frequently disabled by vandals

who

burglarize coin receptacles, left many neighborhoods without

public

communications. Likewise, an increasing number of city residents

living

at or below poverty level while faced with the choice of buying

food or

paying the telephone bill, occupied homes without residential

phone

service. The matter of reliability in the telephone system was

another

concern. A widespread telephone outage would pose serious

ramifications

if the public couldn't get a dial tone. Fire services would

virtually

cease to exist without an effective means to report

fires.

One

viable but costly alternative concerned the replacement of the

mechanical pull box system with electronic voice reporting. Fire

alarm

boxes on the street would be hard wired for voice communications

between

the public and the Fire Dispatcher. A number of cities had

reduced false

alarms by an overwhelming number as a result of adopting such

voice

technology. The premise behind this successful design concerned

a

person's

unwillingness to activate an ERS Box and then stand on a street

comer in

plain view, while engaging the dispatcher in a verbal dialogue

for the

purpose of reporting a malicious alarm. The result of a

feasibility

study to determine project cost for converting the current

mechanical

system proved cost prohibitive in terms of limited capital

funding

relative to other municipal priorities.

As

the City was politically unprepared to abandon the municipal

fire alarm

system in its entirety during 1982, the Fire Administration

decided upon

a policy of selective retrenchment for removing problem boxes

from the

field, With the ensuing removal of dozens, then scores, and

eventually

hundreds of boxes throughout the City during the subsequent

decade, the

rate of malicious false alarms continued to fall each and every

year

from 1983 until 1992 when the few remaining boxes were finally

removed,

dismantling the entire system. The application of risk

management in

balancing the proprieties of public fire protection against the

demands

of fire service operations was the determining factor in the

eventual

elimination of the system. As well, many other major cities

across the

United States would also dismantle their long established

systems in the

interests of operations.

Another

matter involving the judicious application of risk management

concerned

a long-standing problem with the municipal fire hydrant system.

During

the hot summer months, the illegal opening of hundreds of fire

hydrants

created formidable problems for the Fire Control Force. Millions

of

gallons of potable water were bled from the system while

reducing

operating pressures to dangerously low levels. Normal operating

pressures of 50 to 70 PSI, were frequently reduced to as little

as ten

or fifteen pounds residual. Far below the minimum level

necessary to

provide an adequate rate of flow for fire control.

The

Fire Department in conjunction with the Water Department

attempted to

educate the public in the hazards associated with illegally

opened

hydrants, Public education campaigns both in the schools and the

adult

community, endeavored to solicit understanding and cooperation.

The

slogan "Save Water - Save Lives" appearing on bumper stickers

and fire prevention literature, sought to focus upon the

community's

vested interest. Indeed many residents of the City experienced

first

hand, the problems affecting domestic water supplies as hundreds

of

neighborhoods complained about having no water above the first

floor of

buildings, and in not being able to flush toilets or bathe.

Still, the

problem continued to grow worse with each passing summer.

Sprinkler

caps for fire hydrants designed to consume a fraction of the

water, were

distributed by various city agencies but did little to stem the

epidemic

of wide open hydrants. Water Department personnel, Police, and

local

fire companies armed with wrenches, visited hundreds of

locations'

turning off hydrants only to have them repeatedly opened, often

as soon

as the fire company left the scene. Even worse, fire fighters,

water

department employees and even Police were harassed, threatened

and

barraged by rocks and bottles while attempting to shut down

hydrants.

The

occurrence of serious fires during the hot summer months created

extraordinary problems for responding fire fighters. A one or

two room

blaze in a building that should have been handled readily by

just two

hoselines spread to involve multiple rooms or more than one

floor under

conditions of low water pressure. In an effort to obtain the

necessary

volume, fire companies were frequently compelled to connect

apparatus to

more than hydrant. This approach precipitated a demand for

additional

manpower and the need to transmit Greater Alarms for incidents

that

should have been controlled early on, by a first alarm

assignment. At

one particular incident there were so many hydrants open in the

area

surrounding a serious blaze, that the Battalion Chief

transmitted both a

second and third alarm. Second alarm companies were ordered to

respond

directly into the fire, while third alarm companies were

directed to

enter surrounding neighborhoods and shut down hydrants in an

effort to

increase water supplies.

In

a proactive approach, the City began to explore solutions

through

technology, designed to enhance hydrant security and prevent

unauthorized operation. Special types of wrenches, fittings,

outlet caps

and stem configurations were adopted in a never-ending search to

find a

better mousetrap. Over many years, thousands of dollars were

expended by

the City on a wide variety of hydrant security systems, each

producing

limited or less than positive results. In more than just a few

instances

where adopted technology discouraged the opening of hydrants by

unlawful

persons, a twenty pound sledge hammer was brought to bear by

frustrated

individuals, shattering the hydrant ball and rendering the

appliance

wholly inoperable.

During

the nineteen eighties, the Fire Administration recognized that a

radical

solution was necessary in order to avert a disaster in fire

service

operations. Indeed, in recent years and particularly during

periods of

extremely hot weather, the problem in water supplies alarmingly

became

one of volume rather than pressure. The demand for domestic

water

coupled with the opening of fire hydrants began to exhaust

municipal

reservoirs. On several occasions, mutual aid water tankers from

rural

fire companies were summoned to the City as a measure of last

resort. If

the reservoirs ran dry, there would be no water in the system

and

effective fire services would cease to exist. The Fire

Administration's

solution was the shutting off of hydrants at the street valve.

Each

appliance that was turned off at the water main was effectively

rendered

inoperable without the use of a street valve key.

This

extraordinary measure was not without its disadvantages. While

every

fire company was equipped with a five foot long "T" shaped

wrench, having to locate the valve box in the street and then

activate

the hydrant while the fire was blazing, routinely caused some

delays in

obtaining water. At the scene of serious fires, it was not

uncommon to

look down a street for several blocks and see teams of fire

fighters

standing over valve box receptacles at different locations,

resembling

water witches with "T" shaped divining rods in their hands,

looking for water under the ground. Undoubtedly, such delays

resulted in

additional fire spread and some otherwise preventable fire loss.

But the

Department viewed the matter in the appropriate perspective that

delayed

water was far better than no water at all. Certainly an

essential

measure of effective risk management.

During

1983, the Department took delivery of a new Mack Tower

Ladder.

This

seventy-five foot rig was assigned to

Ladder Company

3

and was

particularly well suited for operating at the large two and

one-half

story frame dwellings so peculiar to the

East Camden

and Cramer Hill

sections. A reduction in the number of Greater Alarms for 1983

would

incur a total of 28 incidents or nine less than the previous

year. Total

activity for 1983 remained well Over ten thousand alarms.

Principal

Greater Alarms for the year included:

The

night of May 6th near 11:30 P.M.,

Engine Company

7

turned out for a

verbal alarm from quarters, reporting smoke from the rear of a

commercial building on

Kaighns

Avenue opposite the firehouse. As the

housewatchman opened the station's overhead door, the strong

odor of

rich, acrid smoke was already evident. The Company Officer

ordered a

line stretched and the pumper connected to a hydrant at the

front of

quarters. In moments, heavy smoke was pushing from the front of

a

one-story, commercial type garage building that measured 50 x

100. As

Ladder Company

2 began

forcing a garage door to gain access for the

engine, the interior of the building lit up in roaring fire.

Rows of

occupied dwellings on either side of the blazing building were

saved as

four alarms were transmitted for this Box.

At

7 A.M. on June 26, 1983, a third alarm destroyed a vacant

building at

Broadway

and

Everett

Streets, South Camden. On September 19th, another

third alarm roared through a vacant factory at

Fifth

and

Byron Streets,

North

Camden.

The

last major incident of the year occurred on Christmas morning,

December

25th. Christmas 1983 dawned on a clear, sunny day with frigid

temperatures near the five degree mark. As families everywhere

prepared

to celebrate the solemn holiday, the men in the firehouses

around the

City had settled into what everyone expected to be an uneventful

tour of

duty. Holiday routine as It is traditionally known in the Camden

Fire

Department, are quiet times in the firehouse. Particularly on

special

days like Christmas when the environment of the fire station

with its

concrete floors and the ever present smell of diesel fuel, seem

to

assume a peaceful, even homey atmosphere. The fire fighters are

often

engaged in personal activities - some quietly reading or

watching a

holiday program on television, while still others are busy

preparing the

noon meal for their brothers.

A

few minutes after 10 A.M., the quiet tranquility of the

firehouse was

shattered by the shrill sound of the alarm tones over the

department

radio, followed by the blaring voice of the fire dispatcher

announcing a

structural fire at

Fourth

Street and Lansdowne Avenue, South Camden.

Engine Company

8 and

Ladder Company

2

assigned first due, left the warm

confines of their ancient firehouse and entered the biting cold

of

Kaighns

Avenue

heading west toward

Broadway.

From several blocks away,

they could see the gray and yellow streams of smoke blowing over

the

rooftops. As Engine

Company

8 entered the block, heavy menacing smoke

billowed from the second floor of a two-story dwelling attached

in the

middle of a row of eight buildings. In the bone chilling cold of

the

street whipped by ferocious winds, stood a family of occupants

huddled

together, some wrapped in blankets, as they watched their

Christmas

turned into ashes.

The

absence of integral party walls allowed the fire to rapidly

extend to

adjoining buildings. Battalion Chief Ronald Guernon pulled a

second

alarm on arrival as hose lines were aggressively advanced to the

second

floors of three buildings. Ladder companies armed with roof saws

performed rapid ventilation to stem the spread of fire. As heavy

fire

conditions took possession of the top floors and cockloft of at

least

three buildings, third and fourth alarms were transmitted. Fire

fighters

were punished by the extreme cold and constant battering of gale

force

winds as heavy icing made footing treacherous. Following a two

hour

battle, the flames were finally subdued but not before at least

four

families were made homeless.

Shivering

on the sidewalk, the occupants stared in disbelief at the ruins

of all

their worldly possessions and of what their holiday might have

been.

Near the front windows of one building a Christmas tree could be

seen,

still standing in the corner of a room adorned by once colorful

decorations, now tarnished an ugly brown and coated in real

icicles

where tinsel had hung. Ashes and debris now lay where gift

wrapped

presents had been. As the homeless children wept openly in the

street,

fire fighters went silently about their work knowing that the

real gift

that Christmas, had been no loss of life or injuries to the

occupants.

That the families would live on to enjoy other Christmas Days

together.

During

1984, there would be ten civilian fire deaths, seventy-seven

line of

duty injuries, and twenty-two Greater Alarms.

The

principal incident of the year involved a fourth alarm at a

block long

vacant factory near Delaware Avenue and

Elm

Street, North

Camden, on May

26th. The Box was transmitted shortly after 7 P.M. and first

alarm units

found heavy fire roaring through the roof. At the height of the

fire,

the nearby span of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge became a primary

exposure and traffic between New Jersey and Pennsylvania was

halted for

over an hour. Units remained at the scene throughout the night

following

a five hour battle to control this stubborn blaze.

Like

a majority of other cities, for many years the Department

utilized

station wagons and sedans for Chief Officers and staff

personnel. During

the nineteen eighties, a radical departure from the use of the

automobile emerged in the fire service as an increasing number

of fire

departments began to adopt light duty trucks as personnel

carriers. The

vehicles were far more durable than the auto and particularly

well

suited for heavy use in alarm responses and traversing off road

surfaces. In the Camden Fire Department, the vehicle of choice

became

the Ford Bronco. Its full seating capacity for five persons also

made it

ideal for transporting groups of fire fighters when making

relief

between the station and the fireground. During 1985, the

Department took

delivery of a fleet of eight Ford Bronco trucks.

The first major incident for 1985

occurred at

6:30 A.M. on the cold

morning of January 14th, at Ninth and

Grant

Streets, North

Camden. A

third alarm destroyed several occupied dwellings in a block long

row of

attached buildings. On February 12th, a stubborn third alarm

damaged an

occupied commercial building on Broadway near

Chestnut

Street, South

Camden. In March, another third alarm ripped through a row of

eight

attached dwellings at Second and

Vine

Streets, North

Camden. In April,

yet another third alarm heavily damaged a church on

Benson

Street off

Broadway.

On

July 9, 1985, shortly before 4 A.M., units arrived at the New

Jersey

Transit bus barns at Tenth Street and

Newton

Avenue. The block long

one-story building held over one-hundred buses parked bumper to

bumper,

side by side. Less than four feet separated each column of

parked

coaches. Upon arrival, one bus located several rows back from

the

entrance was heavily involved, threatening to ignite adjacent

coaches

inside the building. Heavy smoke filled the storage bays of the

terminal

and billowed outward from the large door openings at both ends

of the

structure. A second alarm was transmitted as members hustled to

stretch

lines and reach the blazing coach. Ever resourceful, fire

fighters began

to enter the parked buses and drive them out of the terminal on

to

Newton

Avenue. By the time the first due engine had water on

the fire,

a

dozen coaches had been removed from the building and lay

randomly parked

on surrounding streets. The blaze was under control within a

half hour

and the Transit Authority credited fire fighters with preventing

certain

damage to many buses that were removed from harms way.

During

1986, the Department would incur eighty-four line of duty

injuries,

fifteen civilian fire deaths and thirty Greater Alarms. A fleet

of six

new Hahn pumpers and a 100' tractor and tiller aerial ladder

were

delivered to the Department.

Engine Companies

1, 3,

7,

9,

10,

11 and

Ladder Company

2

received new apparatus. During a five month period, more than

fifteen thousand free smoke detectors were installed by local

fire

companies at one and two family residential dwellings throughout

the

City. These detectors were made possible by a funding grant from

the

William Penn Foundation and distribution through the American

Red Cross.

Of

thirty Greater Alarms for 1986, twenty-nine were second alarm

incidents.

A spectacular fifth alarm occurred on August 7th, at 12th and

Fairview

Streets, South Camden.

Engine

Company 10 just three blocks away, arrived

to find a two-story trucking warehouse measuring 200 x 500,

heavily

involved. Pumper relays over distances of one-half mile were

used to

supplement water supplies for numerous master streams. During

the last

month of the year, two church fires would be held to second

alarms by

the aggressive effort of fire fighters. On Christmas Day at

Broadway

and

Viola Streets, rapid line placement and coordinated ventilation

saved

a

large stone church. On New Years Eve near

Broadway

and Spruce

Streets,

and equally aggressive attack by units in the basement of

another church

also saved this edifice from certain destruction.

As

another active year in the city, 1987 would incur eighteen

civilian fire

deaths and eighty-three line of duty injuries. Of thirty-three

Greater

Alarms for the year, the most serious occurred shortly after 1

A.M. on

March 27th at

Baird

and

Admiral

Wilson

Boulevards, East

Camden.

Companies arrived to find

a

five story motel pushing heavy smoke with

reports of numerous occupants trapped above the fire. Second and

third

alarms were transmitted on arrival with a special call for three

additional ladder companies above the third alarm. Numerous

rescues were

made over ladders as the fire spread through void spaces from

the first

to fifth floors. Only one fatality resulted from this near

catastrophe.

Many awards and citations were received as a result of this

incident,

including Unit Citations to two mutual aid companies from

Pennsauken and

Collingswood for their effective work.

On

March 4, 1987 at Second Street and

Atlantic

Avenue, a large vacant

three-story factory went for three alarms and resulted in

several

injuries. Windows above the first floor were sealed with masonry

block

and created serious ventilation problems throughout the

operation. Heavy

smoke conditions blinded fire fighters as they endeavored to

advance

interior lines to reach large quantities of burning rubbish.

Scores of

air cylinders were expended at this incident. On March 23rd, yet

another

church was saved from destruction at a smoky second alarm on

Yorkship

Road near Morgan Boulevard, Fairview. Once again, rapid

deployment of

attack lines coordinated with judicious ventilation, cutoff a

rapidly

spreading fire.

On

April 9, 1987, a third alarm for a row of vacant dwellings kept

units

busy for several hours at

34th

Street and Rosedale Avenue,

East Camden.

On June 3rd, another third alarm in the same block destroyed

some large

vacant frames. Again on June 20th, a second alarm occurred in a

vacant

three-story apartment building on

34th

Street

near

Merriel

Avenue.

Within a two month period, an entire city block of buildings

would be

destroyed in several Greater Alarms and numerous working fires

along

North

34th

Street. Shortly after A.M. on October 23rd, a smoky

second

alarm damaged several classroom facilities at

Camden

High

School,

Park

Boulevard and

Baird

Avenue,

Parkside.

This would be the third Greater

Alarm to occur at a city school for the year.

Principal

Greater Alarms for 1988 occurred during the month of October. At

2 P.M.

on October 26th, a spectacular sixth alarm destroyed a vacant

warehouse

at 17th Street and River Avenue,

Cramer

Hill. The property, a one-story building was one city

block wide

and two blocks long, encompassing

several acres of land. The warehouse was heavily fortified with

chained

metal doors and window openings sealed with masonry block. Upon

arrival,

Engine Company

11

found extremely heavy fire conditions racing through

the building on the River Avenue side. Such access barriers

created

serious forcible entry problems and delayed units in getting

water on

the fire. At the height of the blaze, a huge column of smoke

rising

hundreds of feet could be seen as far as 20 miles away. After

many hours

and numerous master streams, the fire was confined to the

original

building. An adjoining vacant warehouse of similar size was

saved.

Just

five days later on October 31, 1988 at 2:30 A.M., the Box at

East

State

Street and River Avenue was transmitted for a reported

factory.

Engine Company

11

arriving first-due found the adjoining warehouse that had

been saved during the previous sixth alarm, now heavily involved

with

fire extending throughout the block long building. This second

incident

we t for a fifth alarm and leveled the remaining complex. During

January

1988, two church fires within one block of each other near

Broadway

and

Spruce

Streets, South Camden, would be termed arson. The first

fire

occurred on January 6th at 5 A.M. and went for three alarms. The

second

incident on the evening of January 28th was a smoky second alarm

resulting in several injuries to members.

During

1989, the department attended thirty-seven Greater Alarms. The

most

notable incident occurred at the end of the year on the evening

of

December 17th during one of the coldest nights in recent memory.

Engine

9, Ladder

3

and Battalion 2 responded to a verbal alarm for

26th

Street

and

Westfield

Avenue, just one block from the firehouse. A passing

civilian reported fire in a drug store. Units arrived within

moments to

find several stores pushing heavy smoke. A second alarm was

transmitted

as lines were quickly stretched. Metal security gates and frozen

hydrants caused delays in getting water on the fire. As units

forced

entry to rolling security doors, a sea of flame illuminated the

ceiling

area of the store.

The

fire rapidly spread left and right to involve adjoining

properties. The

drug store, interconnected among several other buildings, posed

serious

exposure problems. At the height of the blaze, smoke conditions

were so

severe that the Incident Commander did not know how many

properties were

involved in fire. The Field Communications Unit coming in on the

second

alarm, had difficulty negotiating nearby streets as fire

dispatchers

cautiously made their way through a veil of dense smoke

permeating the

entire area. Fire fighters forced entry to building after

building,

attempting to locate fire extension. An adjoining furniture

warehouse

became the focus of concern as a seventh alarm assignment was

transmitted. Mutual aid units relocating into the quarters of

Engine

9 reported hot embers dropping on the apron of the

firehouse a

block away.

The fire burned throughout the evening, totally destroying the

drug

emporium and heavily damaging two adjoining buildings. Tenacious

efforts

by fire fighters prevented the blaze from extending to the

furniture

store. At daybreak, the fire scene resembled a winter carnival.

Buildings, apparatus, trees and overhead wiring were frozen

solid as the

landscape appeared as virtual ice palaces.

Just

two nights before the East

Camden blaze on December 16, 1989, two third

alarms occurred only blocks from each other. The first at 4:30

A.M.

leveled a row of vacant dwellings near Second and

Chestnut

Streets,

South Camden. Later that evening, another third alarm damaged a

church

near Sixth and

Walnut

Streets. On June 23rd at 8 P.M., a stubborn fourth

alarm on lower

Broadway

near

Morgan

Street destroyed a vacant commercial

building. At 6 A.M. on August 11th, another fourth alarm

occurred at an

occupied warehouse near Eighth Street and Fairmount Avenue,

South

Camden. This fire extended to involve an adjoining row of

occupied

dwellings in a public housing project.

Among

thirty-one second alarms for the year, one particular incident

destroyed

the Cramer Hill Boys Club - a City landmark at

29th

Street and Tyler Avenue,

Cramer Hill. The

clubhouse

was formed in 1954 to discourage

juvenile delinquency. Its sad demise in recent years culminated

in this

blaze that spelled a death knell for the once proud

organization.

Numerous Camden Fire Fighters actively supported this

institution for

many years. Indeed, more than just a few members of the

Department grew

up in the East

Camden and

Cramer Hill

sections as

participating youth.

As Engine Company

11

left the scene of the blaze, all that remained were

gutted ruins among a host of fond, personal memories.

BEGINNING

THE END OF ANOTHER CENTURY

The

last decade of the century would begin for Camden Fire Fighters

like so

many other active years, fraught with heavy fire duty,

debilitating

injury and heroic action. As truly soldiers in a war that never

ends,

the early nineties would recapture a period reminiscent of the

raging

seventies as an increasing number of serious fires honed the

occupational skill of newer members.

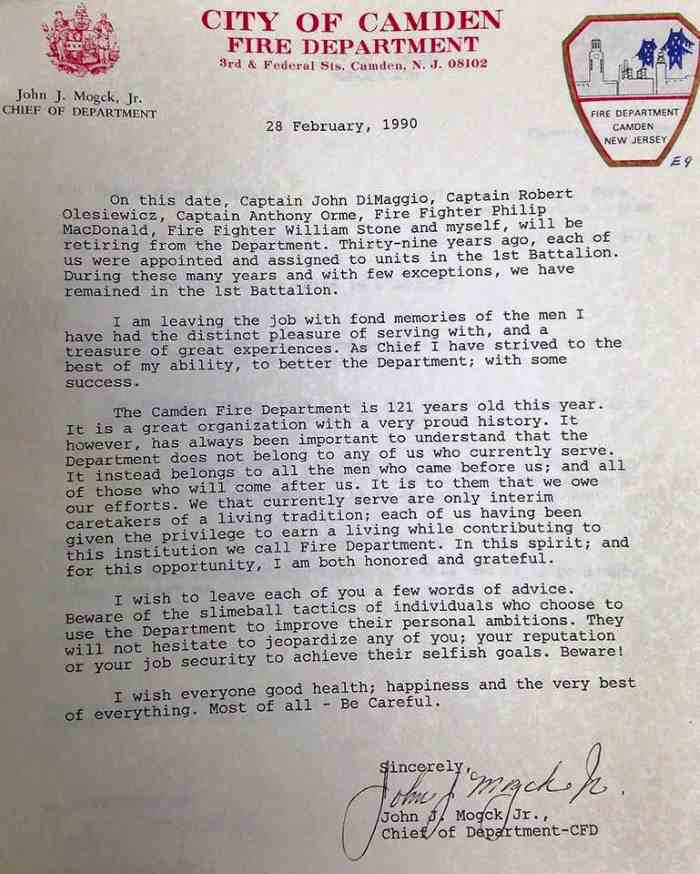

During

1990 and following nearly forty years of service, Chief of

Department

John

J. Mogck Jr. retired upon reaching the maximum age of

service,

stepping down on Mach 1, 1990. Chief

Kenneth L. Penn was appointed as his successor to constitute the

twenty-third Fire Administration in the City of Camden since the

inception of the paid department.

Chief

Mocgk was last a resident of Haddonfield NJ. He passed away on

May 30,

2008, and was buried at the Brigadier William C. Doyle Veterans

Memorial

Cemetery in Wrightstown NJ.

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()