|

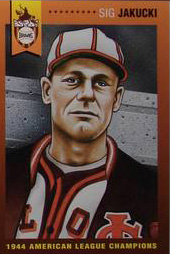

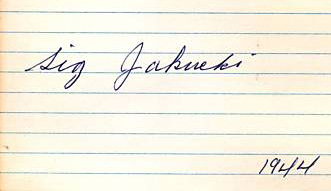

Sig

Jakucki, who was generally known to his teammates as Jack, grew

up to become a 6'2", 198 pound right-handed pitcher who

featured a sinking fastball and a curve ball. He compiled a

25-22 record with a 3.79 earned run average, mostly during the

1944 and 1945 seasons.

Sig

Jakucki played baseball for the

Polish

American Citizens Club in

Camden. In 1927 he enlisted in the United States Army. Stationed

at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii, he became a star slugger and

occasional pitcher for the barracks' baseball team. When his

term of enlistment ended in 1931, he stayed in Hawaii to play

semipro ball, first with the Honolulu Braves and later with

Asahi, team that as author William B. Mead put it,

"was made up of Hawaiians of Japanese descent, Hawaiians of

Portuguese descent, and one hefty towhead of Polish descent

named Jakucki."

Sig

Jakucki became such a star in Hawaii that on the recommendation

of Bill Inman, scout for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific

Coast League, fans paid his way to

San Francisco for a tryout as an outfielder. The Seals were set

with Joe DiMaggio in the outfield, but Jakucki caught on with

the Oakland Oaks. However, he wasn't quite ready for the AAA

level pitching and was let go in May. He caught on with the

Galveston Sand Crabs of the Texas

League, where manager Billy Webb converted him to a full-time

pitcher. He reesponded by posting a 10-7 record in 1934, and won

15 games the following year. Still with Galveston in 1936,

Jakucki had

lost nineteen

games by late August, but pitched well enough to catch the

Browns' eye; they brought

him up. He lost three games, won none, and failed to impress

manager Rogers Hornsby. Bill DeWitt, who was with the Browns at

the time said:

"Hornsby

didn't like the guy, so in spring training of 1937 we sent him

back to the minors. He bounced around from one club to another,

and he'd get drunk all the time, so he got released. Then he

started

pitching

for these semi-pro clubs in Galveston and Houston. He was a

paperhanger and painter during the week and then he'd pitch on

weekends.

We

had forgotten all about him. Then in the spring of '44 we were

short of

pitchers, and this fellow down in Texas told us about him. He

says, 'You better get this guy. He can win some games for you.'

So we got him."

The

Browns sent Sig Jakuki back to Galveston on April 1, 1937. He

had won three and lost six before being sent to the New

Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association. He won twelve

games and lost six. He also made the acquaintance of

ex-Philadelphia Phillie hurler Euel Moore. According to Arthur

Daley in the

New York Times

,

Jakucki

and Euel Moore once went to see a wrestling match after a game.

The hefty, playful Moore had the reputation of being the

strongest man in baseball, and in Jakucki he found a kindred

soul. The wrestling match turned out to be slightly on the

boring side, so to provide some excitement, Moore picked up the

200-pound Sig, and tossed him into the ring. The startled

grapplers thought Jakucki was merely part of the act and that

someone had forgotten to tip them off. But the indignant referee

took a swing at Jakucki, a sad mistake. Jakucki flattened him.

Thereupon the two wrestlers pounced on the interloper, also a

mistake. Moore joined in until the police broke up the

free-for-all and carted Jakucki and Moore to the nearest

jail.

Despite

his winning record, the Pelicans did not bring Sig Jakucki back

in 1938. On February 4 he was sold to the Los Angeles Angels of

the Pacific Cast League, but did not play, and it appeared that

his career as a professional baseball player was over. He

bounced around Texas and Kansas, playing semi-pro ball and

eventually ended up working at a shipyard in Houston.

"Jakucki

would get drunk. He pitched in the National Semi-pro Tournament

in 1940 for Houston Grand Prize beer. They won third place.

Jakucki got stiff, and he got angry at an umpire, and he

accosted him crossing the Arkansas River right outside Lawrence

Stadium

in Wichita, and he dangled the umpire over the rail by his

heels. Oh, he was something, that Jakucki. Luke Sewell had some

real cutthroats to handle."

After

the shipyard job ended Sig Jakucki returned to Galveston where

he worked as a painting and wallpaper subcontractor. When

the Browns surprised Jakucki with a contract, the big

right-hander was 34 years old and had been out of organized

baseball for six years. But he had become something of a legend

in semi-pro ranks. Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post

Dispatch:

Sig

Jakucki clinched the Browns' only pennant with a 5-2 win over

the Yankees on the last day of the 1944 season. His heavy

drinking, however, resulted in his suspension the following

year.

The

1944 baseball season was the peak—or, to look at it

another

way, the nadir—of wartime baseball. The National League

didn't embarrass itself; the Cardinals won their third straight

pennant behind respectable ballplayers like Marty Marion, Walker

Cooper, Johnny Hopp, and especially

Stan

Musial.

But

in the American League, the acute shortage of players dragged

the entire league down to the level of the St. Louis Browns,

perennial doormats who had finished in the second division nine

out of the previous ten seasons. The dismal Browns had never won

a pennant in 43 years of American League competition.

The

1944 Browns were relatively untouched by the military draft, as

they featured an all-4F infield, nine players on the roster 34

years old or older, and a motley collection of notorious

characters, such as Tex Shirley and Mike Kreevich. Sig Jakucki,

who went 13-9 with a 3.55 ERA that year, had as stated above,

was rediscovered pitching for a Houston industrial-league

semi-pro team.

Rounding

out the staff were old men Nels Potter (who went 19-7 with a

2.83 ERA) and Denny Galehouse (9-10), and youngsters Jack Kramer

(who finished 17-13 with a 2.49 ERA) and Bob Muncrief (13-8).

The big hitters for the Browns were 23-year-old shortstop Vern

Stephens, who hit .293 and was second in homers with 20 and

first in RBI with 109, and Kreevich, the team's only .300 hitter

at .301.

St.

Louis won its first nine games of the season, and continued to

surprise the baseball world by hanging tough in a four-team race

with Detroit, Boston, and the Yankees. The race came down to the

final week, when the Browns defeated New York five times,

winning the pennant by 1 game over Detroit.

Jun

29, 1944 - The Yanks move to 2 1/2 games behind St. Louis

with a 1-0 win over Sig Jakucki. Walt Dubiel gives up 2 hits for

the win.

Jul

4, 1944 - Sig Jakucki‚ the Browns 34-year-old rookie‚

threw his 3rd shutout in 4 games‚ blanking the Athletics‚

4-0. Sig has given up 1 run in 27 innings. The win keeps the

Browns 1 1/2 games ahead of Boston. The A's win the nitecap‚

8-3‚ behind Hot Potato Hamlin‚ who strands 10 runners.

Frankie

Hayes has a HR to tie for the AL lead with 9.

Jul

8, 1944 - At Washington‚ the

Browns

edged the Nationals‚ 5-4‚ behind Sig Jakucki. Sig walked

7‚ including 3 intentional walks to

Stan

Spence.

Johnny

Niggeling gives up 10 hits and strikes out 10 in losing

to

the league-leaders.

Sep

26, 1944 - Sig Jakucki pitched the

Browns

to a 1-0 win over the

Red

Sox to keep St. Louis in 1st place.

Oct

1, 1944 - The Browns have their first sellout in 20 years‚

and their largest crowd ever‚ as 37‚815 pack Sportsman's

Park. St. Louis clinches the flag on the final day of the season

by sweeping the series with the Yankees and coming from behind

to win 5-2. The big blows are a pair of 2-run HRs by

Chet

Laabs‚ off Mel Queen. Sig Jakucki was the winning

pitcher.

St.

Louis clinched the flag with victory over New York on two home

runs by Chet Laabs and one by Stephens. The Browns finished with

a record of 89-65, which was, at the time, the worst record ever

by an American League pennant-winner.

The

night before the pennant-winning game against the Yankees, Sig

Jakucki,

who was the scheduled starter, was spotted by Browns' team

trainer Bob Bauman entering the team hotel with a bag of whiskey

bottles. Jakucki was a terrible drinker, and Bauman- seeing the

Browns' first pennant disappear in a Jakucki bender- accosted

the pitcher. "You're not going to take that to your

room", Bauman shouted. Jakucki resisted, and swore he would

not drink that night.

The

next morning, at the ballpark, Bauman immediately realized that

Jakucki had indeed been drinking. Jakucki defended himself: He

admitted he had promised not to have a drink the night before,

and insisted he hadn't. But, he added' "I didn't promise I

wouldn't take one this morning."

Jakucki

proceeded to outpitch the Yankees Mel Queen, and the Browns took

the game, 5-2. The Browns had won the pennant!

The

World Series was another story. Starting Game Four for the

Browns, Jakucki gave up a first inning single to Cardinal first

baseman Johnny Hopp. Stan Musial followed with a two run homer.

Jakucki was touched for another run in the third when Danny

Litwhiler scored on a Walker Cooper single. The Cardinals went

on to win the World Series in six games.

The

Browns were contenders the following season, but fell short for

a variety of reasons. Symptomatic of the Brown's 1945 season

were the events of June 19, 1945.

June

19, 1945 - At St. Louis‚ in what

will be dubbed the "Battle of the Dugouts"‚ the 8th

inning produces fireworks as the

White

Sox score 4 runs to eventually win‚ 4-1. After reliever

George

Caster is lifted‚ he fires the ball into the

White

Sox dugout‚ prompting manager Jimmie Dykes to come out

and

protest.

Browns

catcher

Gus

Mancuso tells Dykes to shut up Karl Scheel‚ a Sox bench

jockey who has been mercilessly "riding" the

Browns.

When Dykes says you can find him in the dugout‚ a few

Browns‚

led by Sig Jakucki and

Ellis

Clary‚ do just that‚ giving a Scheel a "most

brutal" (according to Dykes, that is) pounding. The

ex-Marine required first aid but traveled with the team to

Cleveland. About 100 spectators milled onto the field to try and

see the action. In Cleveland‚ Dykes sent a telegram to Will

Harridge accusing

Browns

manager

Luke

Sewell with instigating the riot.

The

1945 Browns' also featured the big league's only one-armed

player, outfielder Pete Gray. Gray was not a particularly

popular fellow, and Sig Jakucki, who later wound up in prison,

was not always the kindliest of men, either. One story about the

two states that when Gray asked Jakucki if he might help him tie

his shoes, Jakucki replied, "Tie your own goddamned shoes,

you one-armed son of a bitch." The eventually got into an

argument one day and settled it with a fight. Jakucki agreed to

fight with one arm held behind his back.

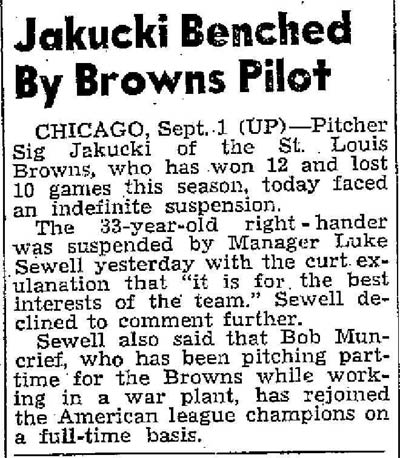

Sig

Jakucki's final game was on August 29, 1945. He started at home

against the league-leading Detroit Tigers, but was taken out in

the third inning by manager Luke Sewell. He proceeded to get

very drunk that night, and showed up late and intoxicated the

next morning at Union Station in St. Louis, from where the

Browns were to travel to Chicago and beyond.

The

Brown's manager Luke Sewell's patience concerning Jakucki's

drinking and behavior, and the Browns play in general finally

wore out on August 30 and August 31, 1945. Although the Browns

were still in the pennant race, the right-hander was given his

unconditional release. Some say that the defensive liabilities

of the one-armed outfielder combined with the release of

Jakucki, who had a 12-10 record at the time, may have cost the

Browns a second trip to the World Series. Without a doubt both

contributed to manager Sewell's decision to quit the

team.

Browns'

trainer Bob Bauman told author William B. Mead of the events

that led to Jakucki's release:

"We

were leaving Union Station in St. Louis around 8 a.m. I'm

standing out there, checking to make sure they all get on the

train. Everybody is there but Jakucki. He comes late; he's

carrying a bag of liquor in one hand and a suitcase in the

other. He couldn't walk straight, he's so drunk.

"Sewell

says, 'You're not getting on thee train. Turn around and go

back. You're through.' Jakucki says, 'No, I'm not. I'm going on

the train.' He drops the suitcase and starts swinging, but he

can't hurt anybody.

"Sewell

got on the train, hollered at me to get on, and told the porter

'Don't let him in the car.' The porter's standing on the

area-way between the two cars. Jakucki climbs up there. He drops

his grip and it breaks the porter's tow.

So

the train starts. Jakucki's between the two cars. Sewell has the

conductor get the police to take him off at Delmar Station [a

passenger station in suburban St. Louis]. Shortest trip in

history.

That

night about midnight, [Brown's Traveling Secretary] Charley

DeWitt gets a call. Jakucki's in the lobby; wants a room. Know

how he got to Chicago? Hopped a freight. They won't give him a

room, so he lays down on one of the divans.

Coming

down in the morning, it was one of the funniest sights I've ever

seen. Here he is, peeking around a corner. He's been sleeping

down in that lobby all night long. He's got a dirty shirt on;

looks like he just got out of jail.

DeWitt

told him he was through with the ballclub. That was where his

career ended."

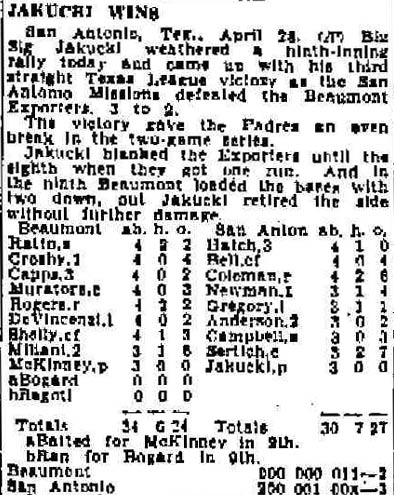

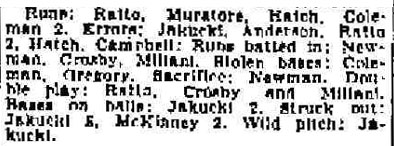

There

were, however, still teams willing to pay Sig Jakucki to play

baseball. He pitched for the San Antonion Missions in the Texas

League in 1946. Still in good form on the mound, he won his

first three decisions, and was still with the team at the end of

the season. The Missions were affiliated with the Browns,

apparently Sig Jakucki had not burned all of his bridges behind

him. On of his teammates on the missions was a young pitcher

named Ned Garver. Garver went up to the majors with the Browns

in 1948. He managed to win 20 games for the big club in 1951,

quite an achievement as the Browns lost 102 games that year.

Garver remains the only pitcher in American League history and

modern baseball history (post-1920) to win 20 or more games for

a team which lost 100 or more games in the same season and the

only pitcher in Major League history to do so with a winning

record.

The

Missions traded Sig Jakucki to the Seattle Raniers in the

Pacific

Coast League after the 1946 season ended. On April 19, 1947 Sig

Jakucki

surrendered a home

run to San Francisco Seals outfield Joe Brovia. Brovia's ball

carried 560-feet over the 40-foot high center-field fence at

Seals Stadium.

Well

into his late 30s, Sig Jakucki could still pitch. His exploits

on and off he field in Seattle were as such- Sig would pitch a

three-hitter and celebrate by taking two or three days

off.

The

Rainier's saintly general manager, Earl Sheely, did his best to

reform him, leading to a perhaps apocryphal story. To keep Sig

out of bars, Sheely would drive him home. One night he drove by

the Rainier Brewery, where the midnight shift was going full

blast.

"See

that, Sig," Sheely said. "You can't drink it as fast

as they can make it."

"Maybe

not," Sig said, "but I got 'em workin' nights."

Things

did not go well for Sig Jakucki after that. He returned to

Houston, Texas where he had been living before the Browns called

him up, and then to Galveston. His alcoholism left him living on

the streets, and begging for what he could. He would

occasionally go to Houston, drop in the city hall to talk over

old times with his old friend Frank Mancuso, who had been a

reserve catcher on the 1944 and 1945 Browns teams. He never

asked for anything, but when the former pitcher was ready to

head back to the streets Mancuso would slip something into

Sig's pocket. Frank was always pleased to see his friend

come in although he might not see him for months. The bottle

ruined Sig's life, and eventually caused his

death.

Sigmund

"Sig" or "Jack" Jakucki passes away on May

28, 1979 in Galveston, Texas at the age of 69. Truth be known,

near the end of his life, Sig had fallen upon hard times due to

bad health and personal problems. He was fortunate to have the

nearby friendship of Frank Mancuso, one of his teammates from

the 1944 Browns American League championship club. Frank Mancuso

pretty much took care of Jakucki in his waning months, including

paying for his burial. Not wanting to feel like a burden upon

Frank, Sig insisted that Frank hold onto his watch as collateral

for the help.

In

later years, when anyone would ask about the beat-up watch,

Mancuso, who had made a career as a politician in Houston would

say “That old ticker has been on my desk for years, and not a

day goes by that I don't look at that old Timex and think of

Sig and the talks we used to have. He was a great pitcher

with lots of potential, he just got lost along the way.”

|