|

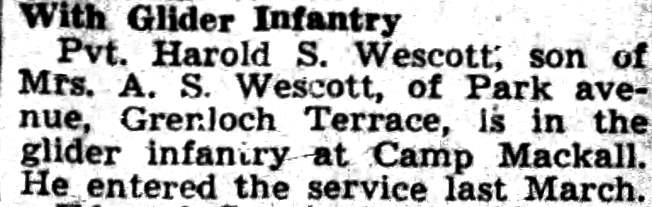

PRIVATE FIRST CLASS HAROLD

S. WESCOTT was the son of Albertus S. Wescott and his wife, the former

Helen Wright Swain. He was born in New Jersey on October 1, 1923. His

father, a veteran of World War I, worked as a house carpenter and as a

contractor. The family was living on Park Avenue in the Grenloch Terrace neighborhood of

Gloucester Township, New Jersey when the Census was taken in 1930. The

1940 Census shows the family at the same address and that Harold Wescott

had gone to work in the building trades.

Harold

S. Wescott was inducted into the United States Army in March of 1943

and, after completing his basic training, was assigned to the Medical

Detachment of 118th Glider Infantry Regiment, 11th Airborne Division.

In

December of 1943, Private Wescott, as part of the 11th Airborne

Division, took part in the Knollwood Maneuver, an exercise mounted

to evaluate the effectiveness of division-sized airborne units. Airborne

units had suffered high casualty rates during the landings in Sicily in

July of 1943, and there was debate as to whether they could be

effectively used.

The 11th Airborne, as the attacking force, was assigned the objective of capturing

Knollwood Army Auxiliary Airfield near Fort Bragg in North

Carolina. The force defending the airfield and its environs was a combat team composed

of elements of the 17th Airborne Division and a battalion from the 541st Parachute

Infantry

Regiment. The entire operation was observed by Army Ground Forces commander Lt. Gen.

Leslie McNair, who would ultimately have a significant say in deciding the fate of the

parachute infantry

divisions.

The Knollwood Maneuver took place on the night of December 7, 1943, with the 11th

Airborne Division being airlifted to thirteen separate objectives by 200 C-47 Skytrain

transport aircraft and 234 Waco CG-4A

gliders. The transport aircraft were divided into four groups, two of which carried

paratroopers while the other two towed gliders. Each group took off from a different

airfield in the Carolinas. The four groups deployed a total of 4,800 troops in the first

wave. Eighty-five percent were delivered to their targets without navigational

error, and the airborne troops seized the Knollwood Army Auxiliary Airfield and secured

the landing area for the rest of the division before

daylight. With its initial objectives taken, the 11th Airborne Division then launched a

coordinated ground attack against a reinforced infantry regiment and conducted several

aerial resupply and casualty evacuation missions in coordination with United States Army

Air Forces transport

aircraft. The exercise was judged by observers to be a great success. McNair, pleased by

its results, attributed this success to the great improvements in airborne training that

had been implemented in the months following Operation Husky. As a result of the

Knollwood Maneuver, division-sized airborne forces were deemed to be feasible, and

Eisenhower permitted their

retention.

Following the Knollwood Maneuver the 11th Airborne remained in reserve until January

1944, when it was moved by train from Camp Mackall to Camp Polk in Louisiana. After four

weeks of final preparation for its combat

role, in April the division was moved to Camp Stoneman, California, and then transferred

to Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea, between

May 25 and June 11. From June to September the division underwent acclimatization and

continued its airborne training, conducting parachute drops in the New Guinea jungle and

around the airfield in Dobodura. During this period, most of the glider troops became

parachute-qualified making the division almost fully Airborne. On

November 11 the division boarded a convoy of naval transports and was escorted to Leyte

in the Philippines, arriving on

November 18. Four days later it was attached to XXIV Corps and committed to combat, but

operating as an infantry division rather than in an airborne capacity. The 11th Airborne

was ordered to relieve the 7th Infantry Division stationed in the Burauen-La Paz-Bugho

area, engage and destroy all Japanese forces in its operational area, and protect XXIV

Corps rear-area supply dumps and

airfields.

Major General Swing ordered the 187th Glider Infantry Regiment (GIR) to guard the rear

installations of XXIV Corps, while the 188th GIR was to secure the division's rear and

conduct aggressive patrols to eliminate any enemy troops in the area. The 511th

Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR) was assigned the task of destroying all Japanese

formations in the division's operational area, which it began on 28 November when it

relieved the 7th Infantry. The 511th PIR advanced overland with two battalions abreast

and the third in

reserve, but progress proved slow in the face of fierce Japanese resistance, a lack of

mapped trails, and heavy rainfall (with more than twenty-three inches

falling in November alone). As the advance continued resupply became progressively more

difficult; the division resorted to using large numbers of Piper Cub aircraft to drop

food and

ammunition. Several attempts were made to improve the rate of advance, such as dropping

platoons of the 187th GIR from Piper Cubs in front of the 511th PIR to reconnoiter, and

using C-47 transport aircraft to drop artillery pieces to the regiment's location when

other forms of transport, such as mule-trains,

failed.

On December 6, 1944 the Japanese tried to disrupt operations on Leyte by conducting two

small-scale airborne raids. The first attempted to deploy a small number of Japanese

airborne troops to occupy several key American-held airfields at Tacloban and Dulag, but

failed when the three aircraft used were either shot-down, crash-landed or destroyed on

the ground along with their

passengers. The second, larger, raid was carried out by between twenty-nine and

thirty-nine transport aircraft supported by fighters; despite heavy losses, the Japanese

managed to drop a number of airborne troops around Burauen airfield, where the

headquarters of 11th Airborne Division were

located. Five L-5 Sentinel reconnaissance aircraft and one C-47 transport were

destroyed, but the raiders were eliminated by an ad hoc combat group of artillerymen,

engineers and support troops led by

Major General Swing.

The 511th PIR was reinforced by the 2nd Battalion, 187th GIR, and continued its slow but

steady progress. On

December 17 it broke through the Japanese lines and arrived at the western shoreline of

Leyte, linking up with elements of the 32nd Infantry

Division. It was during this period that Private Elmer E. Fryar earned a posthumous

Medal of Honor when he helped to repel a counterattack, personally killing twenty-seven

Japanese soldiers before being mortally wounded by a

sniper. The regiment was ordered to set up temporary defensive positions before being

relieved on December

25 by the 1st Battalion, 187th GIR, and the 2nd Battalion, 188th GIR, who would

themselves incur considerable casualties against a heavily dug-in enemy. The 511th PIR

was reassembled at its original base-camp in Leyte on 15 January

1945.

On January 22 the division was placed on alert for an operation on the island of Luzon,

to the north of

Leyte. Five days later the 187th and 188th Glider Infantry Regiments were embarked for

Luzon by sea, while the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment flew by C-46 Commando

transport aircraft to Mindoro. At dawn on

January 31 the 188th GIR led an amphibious assault near Nasugbu, in southern Luzon.

Supported by a short naval barrage, A-20 Havoc light bombers and P-38 Lightning fighter

aircraft, a beach-head was established in the face of light Japanese

resistance. The landing was very dangerous. The seas were too calm, and the

artillery supporting the 188th could not get ashore to suppress Japanese firepower.

The regiment moved rapidly to secure

Nasugbu, after which its 1st Battalion advanced up the island's arterial Highway 17 to

deny the Japanese time to establish defenses further inland. The 2nd Battalion moved

south, crossing the River Lian and securing the division's right

flank. By 10:30 elements of the 188th had pushed deep into southern Luzon, creating the

space for the 187th GIR to come ashore. The 188th's 2nd Battalion was relieved and the

regiment continued its advance, reaching the River Palico by 14:30 and securing a vital

bridge before it could be destroyed by Japanese combat engineers.

Following Highway 17 to Tumalin, the regiment began to encounter heavier Japanese

resistance. At midnight the 187th took over the lead and the two glider infantry

regiments rested briefly before tackling the main Japanese defensive lines. These

consisted of trenches linked to bunkers and fortified caves, and were manned by several

hundred infantry with numerous artillery pieces in

support. At 09:00 on February 1 the glider infantry launched their assault, and by

midday had managed to break through the first Japanese position; they spent the rest of

the day conducting mopping up operations.

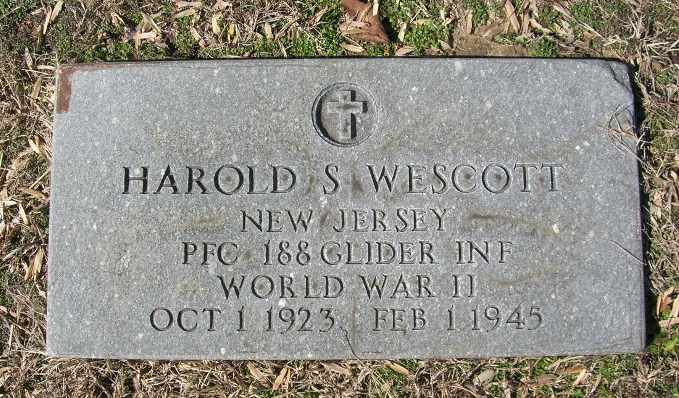

Private

First Class Harold S. Wescott, serving with the Medical Detachement of

the 188th Glider Infanrty Regiment, died on February 1, 1945 of wounds received in

combat

during the Nasugbu beach operation. He was awarded the Bronze Star

posthumously.

Harold Wescott was brought

home in September of 1948 aboard the

USAT Sergeant Morris E. Crain

. He

was buried at the Bethel

Methodist Episcopal Church Cemetery, 481 Delsea Drive in the Sewell

section of Washington Township, New Jersey. Private Wescott was survived

by his parents, brother Albertus C. Wescott and sister Helen Wescott.

|