CAMDEN, NEW JERSEY

HEROES of

CAMDEN, NEW JERSEY

![]()

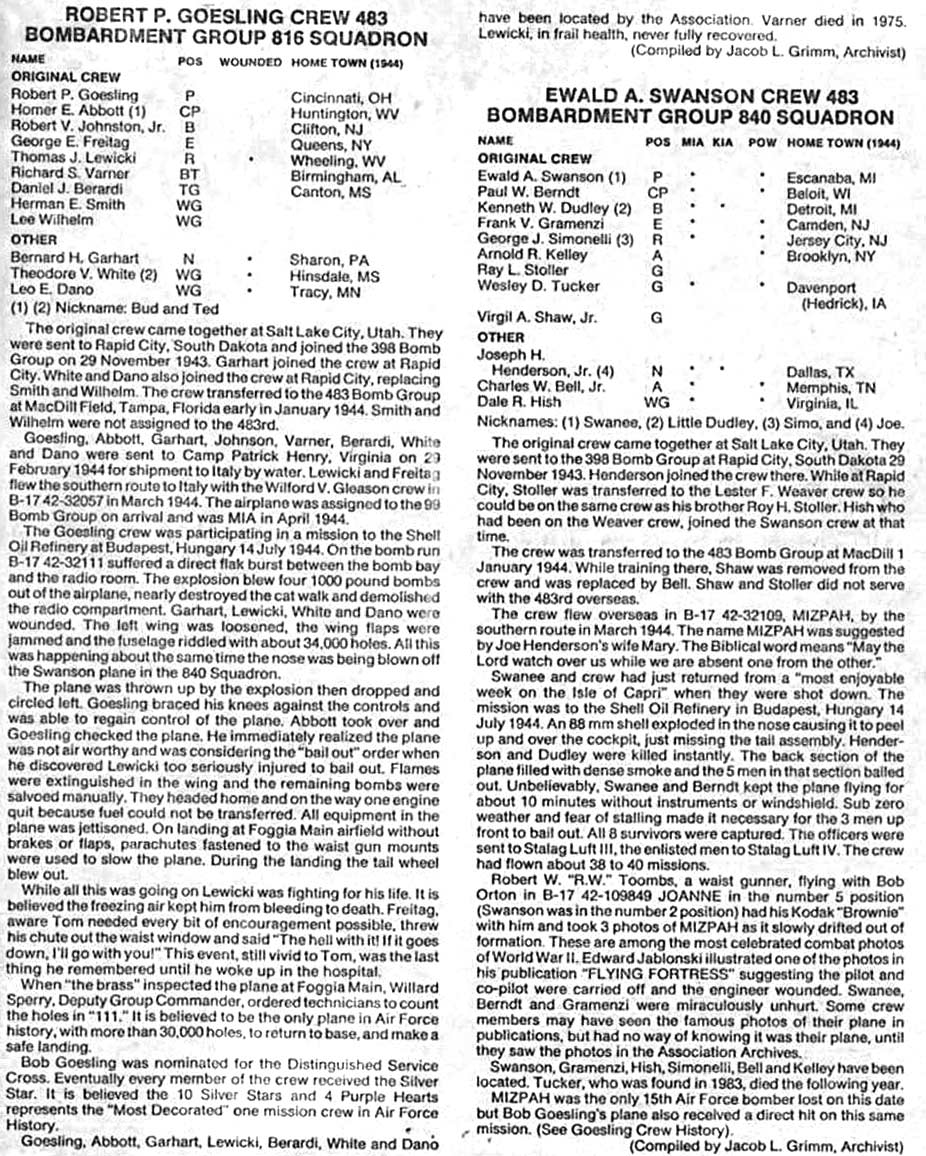

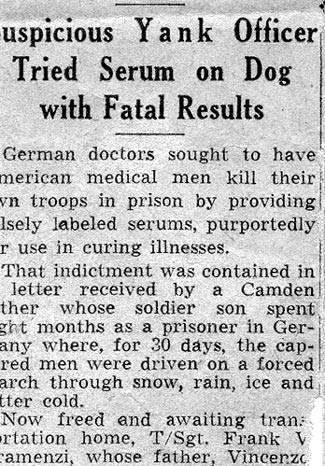

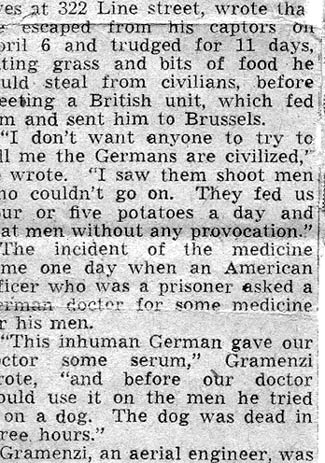

====================================================== Hello All: Today, it being Veterans Day, this is in memory of my father, Frank V. Gramenzi….. My father was a Flight Engineer on the “Ewald Swanson Crew 483 Bombardment Group 840 Squadron” (see article below right column). The name of my father’s B-17 was the MIZPAH. The MIZPAH was shot down July 14th, 1944, over Hungary. We have the framed photographs below which were t aken by Robert W. Toombs who was flying in another B-17 called the My father’s B-17 is the plane with the nose blown off. He had no idea the photographs had been taken until some time in the 1950’s. The arrow on the bottom photo points to where my father parachuted out only to be captured upon landing. He was in a German prison camp for 11 months along with his surviving crew members. Incredibly, my father escaped somehow and made it back to safety. Thought you would enjoy seeing the photos. Rochelle

Gramenzi |

||||

| ONE MISSION, TWO MIRACLES |

|

| Camden Courier-Post * April-May-June 1945 | |

|

|

|

|

|

AMERICAN PRISONERS

OF WAR IN GERMANY Strength: 1482 AAF NCOs Location: Pin Point: 53-55 N, 16-15 E. the camp is at Gross Tychow, Pomerania, 20 kilometers southeast of Belgard Description: Opened to Americans on May 12, 1944, this new camp is only one quarter completed. Its eventual capacity will be 6400. POWs are living in new wooden barracks where ventilation is at present insufficient, but will be improved soon, according to the German Commandant. Bathing facilities are not yet finished and POWs are unable to bathe. Toilet facilities are adequate. The Swiss delegate thinks the camp will be satisfactory when completed. Treatment: Poor Food: POWs complain about the food situation. They do not handle the administration of Red Cross Parcels and have asked the Swiss delegate to protest against the present system to German High Command. In addition, the camp lacks facilities for individual preparation of Red Cross Food. Clothing: Clothing supply is insufficient; pending arrival of Red Cross shipments. Health: Two American doctors are in charge of the temporary camp infirmary. Need of a dental office has been foreseen, but none…installed. Religion: A chaplain has been requested. Personnel: Unknown Mail: Mail arrives irregularly. Recreation: A sports field lies within the camp. There is no organized recreation. No theater, no canteen. YMCA representatives recently visited camp. Work: NCOs are not required to work Pay: Not known

Report

of the International Committee of the Red Cross Camp Leaders: Sgt. Richard M.

Chapman (American) Strength: 7089 Americans: 2146 in camp A

886 British: 606

British Isles General remarks: The first 64 arrivals entered Stalag Luft IV on May 14, 1944. Two weeks later, Stalag Luft IV was officially opened. Since then the strength has continually increased by arrivals of small groups of about a hundred men, until July 18th and 19th; on which date the strength was doubled by the arrival of 2400 Americans and 800 British from Stalag Luft VI. The strength reached the present figure by groups coming from Wetzlar and, each week from Budapest… Except for the medical personnel, the chaplains and 9 privates of the British Army, the prisoners are all American and British NCOs. Situation: Stalag Luft IV is situated about 20 Kilometers to the south of (Belgard) and is placed in (the center of a) clearing… Accommodation: The camp is divided into five distinct parts separated by barbed wire fences. Camps ( compounds ) A, B and C contain Americans only. Camp D contains American and British. The main camp (vorlagar) includes the infirmary, food and clothing storerooms. Today, Stalag Luft IV has twice too many inmates. The men are housed in forty wooden huts, each hut containing 200 men. The huts are only partially finished; new arrivals are expected and more huts are being erected. The dormitories have been prepared for 16 men in two tiered beds. But there are not sufficient beds for some rooms contain up to 24 men each. At camps A and B , a third tier of beds has been installed, whereas beds have been removed from camp D. There is not a single bed in camp C and 1900 men sleep on the floor. 600 of them have no mattress, only a few shavings to lie on. Some have to lie right on the floor. Each prisoner has two German blankets. None of the huts can be properly heated. The delegate only saw five small iron stoves in the whole camp. Some of the huts in camp D have no chimneys. Each camp has two open air latrines and the huts have a night latrine with two seats, The latrines are not sufficient as they are not emptied often, the only lorry for this work being used elsewhere. The prisoners have no means of washing; there are no shower baths as there is only one coal heated geyser in the camp of 100 liters for 1000 men. Fleas and lice are in abundance; no cleansing has been done. Food: The German food is no worse than at other camps. The first day of the delegates visit, the men had received bad meat, which was however, taken back again and the next day the meat was quite fresh. On the other hand, prisoners cannot check the distribution of rations, the official weekly menus not having been posted in the camp. Each camp has a kitchen for preparing German rations, except the main camp ( Vorlagar ). Each camp has five or six cooking utensils, holding 3000 liters; these utensils are sufficient for cooking German rations, but there are no means of cooking food from collective consignments, which it is forbidden to prepare outside the kitchens. Collective consignments – Food: Since Stalag Luft IV has been opened, camp leaders have never been in a position to make proper check on the arrival and distribution of collective consignments, which was still possible recently in other camps in Germany. The camp Commandant has taken no account of the camp leaders complaints regarding this matter and the latter are not allowed to be present when the consignments arrive at the station. The distribution is entirely dealt with by the camp authorities, who distribute supplies or stop them on their own initiative. The same applies to the invalid food parcels, part of which are stored with the other Red Cross Parcels; doctors have no access to Invalid Parcel stocks. The ten last consignments form Geneva were handled without any checking by the camp leader who, when the corresponding receipts were presented to him for signature on Aug. 28, refused to sign them…. Five wagons of American food parcels arrived in the camp at the beginning of August. On September 17th, the contents of the wagons were shown to the camp leaders and they were informed that the trucks had been opened and that the total number of parcels had not arrived. As already mentioned, Stalag Luft VI was evacuated on July 14-15. The collective consignments on July 12th was 52,000 parcels. Prisoners received 12,000 parcels to take with them to the new camp and the 40,000 remaining parcels were to have been equally divided between the two new camps, when evacuation had finished. Up to this day, the 20,000 parcels due for Stalag Luft IV have never arrived. It is not possible to state if Stalag 357 (to where most of the British were evacuated) received the parcels, which should have been sent there. It is feared that those 40,00 parcels will never reach their proper destination. It must also be said that a great number of the 6000 parcels, which the prisoners brought with them from Stalag Luft VI, must have been lost (in view of the very bad conditions in which the journey took place, when the new prisoners were obliged to abandon a great number or had them taken away). On account of this shortage, the American prisoners at Stalag Luft IV have had to go on half rations since their arrival, except for a period of two weeks. The Americans still have 10,00 parcels, making a week and a half reserves. On the other hand, the British have about 7000 parcels which would cover their needs over four and a half months with the new system of rationing. British prisoners had to abandon over a million cigarettes and 150 kilos of tobacco during the transfer from one camp to another. Up to present, only a quarter of these cigarettes has been issued to prisoners (British and American). Clothing Clothing consignments, which should have arrived at Stalag Luft IV, have also not been spared. On leaving Stalag Luft VI, each prisoner had a proper outfit. There remained in camp about 2500 pairs of boots, 3000 tunics, 2500 trousers, 3000 shirts, and many other articles. Up to the present nothing has been rendered to prisoners of Stalag Luft IV except 155 pairs of boots, although they are in great need of clothing. They also had to abandon a great deal of their clothing on the way or it was taken from them upon their arrival; up to now, only a part of the clothing has been given back. The same applies to the Red Cross bags, which are indispensable for storing clothing. Prisoners coming from Wetzlar had the same experience. A great many prisoners from Luft VI have not been able to change their clothes for over a month and have been deprived of their toilet requisites. The camp leaders have no control over clothing stocks at Stalag Luft IV. They could not therefor discuss this matter with the delegates; they have never been shown notices of arrival of such consignments from Geneva. Distribution is entirely in the hands of the camp authorities and the needs of each camp are not taken into account. When distribution takes place, the camp leaders are not asked to state the quantities required. There is urgent need for the distribution of great coats and warm clothing for the prisoner’s comfort in the cold season, which has just started, especially in view of the lack of heating. Generally speaking, the prisoners clothing is in bad condition; they are very short of underclothing, due in some instances the fact that shirts from the British Red Cross consignments have not been distributed… In this connection it must be mentioned that in many cases, and especially in camp A, German workmen were met, who wore American effects. On Sept. 23rd a lorry and three trailers left (the Vorlagar) with new American clothing sent by the Red Cross. Medical Attention: Senior American

Medical Officer - Capt. Henry Wynsen M.C. Besides the two doctors mentioned, there are an American Doctor, a British Doctor and British Dentist working in the infirmary, also 14 medical personnel. The infirmary has 132 beds, which figure represents 1 ¼ % of the camp strength. This figure should be at least 3% for 8000 prisoners, i.e. 240 beds. The infirmary is full up and slight cases have to be left in the huts. Such slight operations as opening of abscesses, local anesthetics, intravenous piqures and so forth are carried out in a small operating ward. More serious cases are sent to Stargard or Belgard hospitals. The general state of health is not bad. The doctors complain of the frequency of skin trouble, which cannot be avoided with the present deficient sanitary arrangements. There are not sufficient medical supplies and the doctors would be grateful if a large quantity of medical supplies and instruments could be sent… There are not sufficient medical personnel, but it’s not recommended to ask for personnel from other camps. There are enough qualified medical assistants among the airmen, who would be quite prepared to help, if authorized by the camp authorities. Next to the infirmary are two huts, one of which is used principally by the medical personnel. The doctors are shut into their rooms at 6pm and cannot come out until the next morning. Medical attention to patients in the second hut is difficult on account of this ruling… An American doctor, Capt. Wilber McKee who assisted in the infirmary, is on bad terms with the Camp Commandant. He is forbidden to practice. Recreation, intellectual and spiritual needs: Classes were started on September 18, 1944 at Stalag Luft IV. Groups were organized and specialists teach all branches. There are classes in English literature, French conversation, Italian for beginners, physiology, practical science, aviation, navigation, etc. It must be pointed out that on account of the distance between the four different camps, this organization can only benefit a part of the camp. The above details apply to camp D for British and Americans. Up to now 318 students have entered for classes. No classroom being available, classes are held in laundries and huts for two hours in the morning and afternoon; 43 students from various Universities are preparing for examinations. There are 246 students in camp D.. They are short of writing materials and have to use cigarettes and wrapping paper.. The YMCA recently sent them a small parcel of pencils, but they are still greatly in need. The camp has a technical library of 1900 books brought from the general library at Stalag Luft IV. Needs: As in other camps, the student’s request past examinations papers especially those of London University. The Royal Society of Arts… etc. No sport is possible for the few sport requisites, which the prisoners were able to bring with them from the former camp, can no longer be used. There are several excellent musicians (at) these camps, but they have unfortunately no instruments. A jazz band at the camp B, which included first class musicians, only possesses a chromatic accordion, a double bass and a guitar. Three chaplains are attached to the camp: Capt. Rev. T.J.

B. Lynch - Catholic chaplain Religious services are held in a room called the Red Cross Room which serves for various other purposes (storing books, clothes etc). The room is unfortunately not large enough to hold many prisoners wishing to attend. The Catholic chaplain urgently requests the return of certain church furnishings, which were taken away during the transfer from one camp to another. He is particularly anxious concerning his consecrated altar, and his personal copy of the New Testament. The chaplains also report that a great many prisoners were deprived of their religious tokens on arriving at Stalag Luft IV and that these tokens have not been given back. They further complain that they cannot journey from the different camps to accomplish their ministry. Their activity is greatly hampered by the fact that they may only go from one part of the camp to another accompanied by sentries. They also experience difficulties once on the way. The Protestant chaplain also complains of the confiscation of Bibles, religious books and church furnishings. He also has great difficulty in carrying out his ministry. The Protestant Chaplain Jackson, civilian internee, has been deprived of his black cassock, which has not been returned in spite of repeated requests. He is obliged to wear a grey coat and carries out his ministry, when the camp authorities give him the possibilities of doing so. Mail: As in other camps, the mail service is affected by actual circumstances. The prisoners however, are inclined to consider that no steps are being taken to help matters. Mail leaves the camp once a week. The camp leaders complain that they are not allowed to wire to Geneva. Conclusion: Stalag Luft IV is a bad camp although the situation, the accommodation and the food do not differ from those in other camps… Final interview with Camp Leaders: Before leaving camp the delegate was allowed to again see American camp leader Chapman and the British Camp leader Clarke and inform them of the result of his recent interview with German officers… The American Chapman came to camp in May with the first arrivals. He was officially in charge until the large number of prisoners from Luft VI necessitated the election of an American Camp leader Paules (who had previously acted as Camp Leader at Luft VI and who was elected to do so with a 90% majority). The camp Commandant never sanctioned the vote and would not change his attitude… Mr. Chapman declared in a letter written during the delegates visit addressed to the Commandant that he never considered himself to be American Camp Leader, consequently he could not be recognized by Geneva. He therefore resigned his temporary duties in favor of his comrade Paules, whom he greatly esteems and whose qualities he appreciates. The delegate asked him to remain in office, in the American prisoner’s interests, and requested Mr. Chapman to bear his heavy burden in cooperation with his comrades.

Deposition

of Capt. Henry J. Wynsen On 20 July 1945, Capt. Henry James Wysen, Youngstown, Ohio, was interviewed regarding hospital facilities at Stalag Luft IV, Pomerania, and also as to general conditions existing at the hospital and in the prison compounds. Wynsen was a Prisoner of War of the German Army from November 1942 to 26 April 1945. He was held at Stalag Luft IV, Gross Tychow, Pomerania from June 1944 to 6 February 1945. He was required to work in the camp hospital, rendering such assistance to American Prisoners of War, as he was able. Wynsen described Stalag Lift IV as consisting of four lagers, named A, B, C and D. Each lager was made to accommodate approximately sixteen hundred 1,600 prisoners, but crowding pushed the lager count from 2,300 to 2500 each. The total camp strength by January 1945, was approximately 10.000 prisoners. Rooms in barracks were at least fifty per cent (50%) overcrowded. Men were required to sleep on the floors and tables. The barracks were new but they were very difficult to keep clean because of lack of brooms, mops, and cleaning materials. The barracks were inadequately ventilated because of blackout regulations prohibiting the opening of windows and doors. Latrines: Each barracks had inside two-hole latrines with urinals to accommodate two hundred and forty (240) men. Each lager had two outside latrines with approximately twenty (20) holes each. Each latrine was a cement lined stagnant pit, drained periodically by Russian Prisoners of War. This was drained and spread on a field adjacent to the camp. Water: Each compound had two large outside wells with pumps. This provided the drinking and washing water for the compound. According to German doctors, samples of the water were tested periodically and results showed the water to be potable. While at this camp, there were no cases of typhoid or cholera. Bathing: There were no facilities available for bathing or delousing* Each barracks room had a pan for washing hands, face, body, and dishes. All water had to be carried into the barracks from the pumps outside in the compound. Parasites: Fleas lice, scabies, and bed bugs were common. The Germans furnished no insecticide or delousing powder. There were no cases of typhus in the camp. Food: Food consisted of daily ration of bread (approximately 300 Grams), margarine (30 grams), and plain boiled potatoes or a soup mixture made up of potatoes, and some other vegetables; usually cow turnips, carrots, or dehydrated sauerkraut. Meat allowance was 15 grams (one-half ounce) daily. Barley was usually served every week. Cheese and ersatz jam was an occasional issue. Sugar (100 grams) was issued once each week. When Captain Wynsen arrived at Stalag IV, all Red Cross suppliers (food, clothing, and medical supplies) were under direct control of the Germans. The Germans refused to tell Cpt. Wynsen how many parcels were available in camp. It became necessary to make direct protest to the Red Cross representatives, but this was not effective. Captain Wynsen stated he estimated the prisoners at this camp received 1,200 calories of food daily. He arrived at the estimated number of calories, by using all food contained in Red Cross parcels, as well as, food furnished by the Germans. Clothing: While Captain Wynsen was at Stalag Luft IV, no American or British soldier was ever Issued any German clothing, socks, underwear, etc. It was the policy of German officers and enlisted men, at this camp, to purposely hinder the issuance of Red Cross clothing to American Prisoners of War. Medical and Dental facilities: The hospital at Stalag Luft IV consisted of two buildings with a total bed space of 133 beds. The number of beds available at this hospital was not sufficient to render proper medical care to the 10,000 men imprisoned at this camp. Shortage of hospital beds made adequate treatment difficult. At times patients were required to sleep on the floor, because of the bad shortage. In order to make room; the German doctor would sometimes discharge patients who were not well, in spite of protests of Cpt. Wynsen and other American and British doctors. Wynsen cited one case in which an American Prisoner, by the name of Steele, who was suffering from jaundice, was ordered out of the hospital by a German doctor, in spite of protests made. Several days later, Steele was readmitted to the hospital, in worse condition. Drugs, Supplies and equipment: The hospital had double-decker beds, except for a few single iron cots. There was one bathtub in the hospital. When Wynsen arrived at Stalag Luft IV, the hospital had bed sheets, but later on, while he was there, bed sheets were denied the hospital except where it was absolutely necessary for skin diseases. The dispensary was fairly well outfitted for medical examinations, treatment and minor surgery. There were no facilities for major surgery. All x-ray patients and major surgery patients had to be sent elsewhere as they could not be accommodated at the hospital. Sick call was held from 1030 hour to 1200 hour daily, in the lagers. Each. Lager had a make shift dispensary. Medical officers were accompanied to sick call by German guards and an English speaking interpreter. Germans generally gave a weekly issue of drugs. Influx of American and British Medical parcels was good and these, together with the German issue, made medical supplies adequate (except for such items as diphtheria anti-toxin, syringes, gauze and thermometers). Dental Facilities: There was one British dental office, at this camp. Dental equipment was brought from the German revier to the Prisoner of War hospital, two or three time per week. There were practically no facilities for repair of bridgework. Silver alloy was difficult to get. Novocain was available. Confiscation of medical Books: When Captain Wynsen arrived at Stalag Luft IV, 28 June 1944, his medical books, clothing and fountain pen were confiscated by the Germans. He was told that these would be returned to him very shortly. In spite of aII protest, the Germans refused to return these items and told him that he should be glad to be live. The medical books were returned to Captain Wynsen, the first week in September 1944. Bayoneting and Injury to Prisoners in the Course of "Runs" from Railroad Station to Stalag Luft IV: Captain Wynsen stated that on 17, 18, 19 July and 5 and 6 August 1944, he and Cpt. Wilber McKee treated injured American and British soldiers, who had been bayoneted, clubbed, and bitten by dogs, while on route from the railroad station to Stalag Luft IV, a distance of approximately three (3) kilometers. Most of the injuries were bayonet wounds, which varied from a break in the skin to punctured wounds three inches deep. The usual site was the buttock; hit sites included the back, flanks, and even the neck. The number of wounds varied from one to as many as sixty. One American soldier suffered severe dog bites on the calves of both legs, necessitating months of treatment in bed. The first bayonet patient seen by Dr. WYNSEN was in a hysterical condition with a punctured bayonet wound in his buttock. A medical tag was fastened to his shirt with a diagnosis of " sun stroke". For his "sun stroke" the man had been given tetanus anti-toxin. This diagnosis was made by a German Captain named Summers. None of the American prisoners died of bayonet wounds. It was estimated that there were over one hundred American and British bayoneted during the course of these runs to the Stalag. General Physical Condition of Prisoners: At no time was the camp without Red Cross food. The physical condition of the prisoners was fair. There were no cases of severe malnutrition. The average lose of weight per man was approximately fifteen pounds, up to the time of a forced march on 6 February 1945, at which time a portion of the camp personnel was evacuated. Locking up of Medical Personnel: When Cpt. Wynsen arrived at Stalag Luft IV in June 1944, prisoners were locked up at approx. 2130 hours. As the winter months approached and daytime shortened, the lock up time came earlier and by November 1944, the entire camp, including medical personnel, were looked in from 1600 hours to 0700 hours the next day. The working time for the doctors was limited from 0700 to 1600 hours. This was insufficient time for proper medical care of patients. After 1600 hours, patients in one hospital building could not be visited or attended by medical personnel living in the adjacent hospital buildings. These security regulations were not lifted, in spite of strong protests, until January 1945. In January, medical personnel were permitted to walk from one hospital building to the other until 2100 hours, provided they wore the Red Cross brassard on their arm. Diseases Suffered by Prisoners of War: 1. Upper Respiratory: Coryza, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, grippe. 30% to 40%. 2. War wounds to include fractures, 15% to 20% 3.Gastrointestinal. Diarrhea: 5%

average but as high as 50% during month of July. No typhoid,

amoebiasis, or true dysentery. 4. Skin diseases:10%. furunculosis, pyoderma from infected scabies and lice bites were the most common. Trichophyton infection extremely common in summer months. 5. Contagious: Diphtheria: 3% to as high as 10%, with approximately 20% complicating post-diphtheria paralyses. One emergency trachetomy. No deaths. 6. Jaundice: l% 7. Tuberculosis: Captain Wynsen had none, but other doctors had several cases. Ono death from miliary tuberculosis ending in tuberculosis meningitis. Miscellaneous:10% Paronychiae, hemarrhoeds, polyarthritis, arthritis, etc. German Medical Personnel at Stalag Luft IV, Pomerania: Captain Summers (other possible spellings: Sommer or Sumer) was a medical officer and a captain in the Luftwaffe (Stabsarzt). Sommers was about forty years of age, five feet ten inches tall, had black hair, graying at the temples. He spoke some English, but would not admit it. He was chief of Prisoner of War Hospital at this camp. Birtel was a German sanitator, born in Vienna of Austrian descent. He was about fifty years of age, six feet tall, and weighed from 150 to 160 pounds He spoke good English, but had an accent. This man learned to speak English in China. He wore glasses for reading, but did not wear them all the time. He had dark hair, which was graying, a long thin face, and gray eyes. Birtel was a medical orderly with rank of Pfc. He was liaison man between Prisoners of War and German doctors. Excerpt from

S./Sgt. Bill Krebs deposition William A. Krebs; formerly: Staff Sergeant. ASN , United States Army now residing at Ellwood City, Pennsylvania. was interviewed on 10 June,1947 and stated in substance: I entered the Army of the United States in October, 1942 and went overseas to the European Theatre of Operations in 1943, and was subsequently assigned to the 385th Bomber Group. On or about 31 January 1944. while I was acting in the capacity of engineer-gunner on a B-17, and on bombing mission over Germany., our crew was forced to bail out of the plane and -parachute to the ground. I was captured a few hours later by German troops near Minden, Germany., and taken to Dulag Luft. At Dulag Luft I was interrogated and from there was sent to Stalag Luft 6, where I remained for approximately six months. While I was at Stalag Luft 6, 1 was not mistreated. From here I was next transferred too Stalag Luft 4 and remained there for approximately Six months. All prisoners of war at. Stalag Luft 4 were treated harshly and their wishes or desires given little or no consideration, Since I speak German fluently, I acted as an interpreter at this camp Among the German officers and non-commissioned officers at Stalag Luft 4 who mistreated American prisoners of war were Oberst Leutnant (Lieutenant Colonel). Aribert Bombach, the commandant of the camp; Hauptmann - (Captain) Walther Pickhardt, the camp security officer; and Feldwebel (Sergeant) Reinhard Fahnert, who had direct charge of the prisoners. Click here to see Deposition by Frank Paules (camp leader of Stalag Luft IV) regarding Otto Bombach, Reinhard Fahnert, and Walter Pickhardt. Reinhard Fahnert had charge of the prison guard and supervised the distribution of food to the prisoners. Fahnert was a rough character, and was always after, anyone of Jewish extraction. He wanted to segregate all Jewish prisoners from the others in order to give them all the hard work and menial tasks. We had been previously searched at Stalag Luft 6, and were allowed to keep all of our personal belongings. However at Stalag Luft 4 we-were all lined up outside the barracks by Fahnert and his assistant, a man by the name of Schmidt who we had nicknamed "Big Stoop They would go through the barracks Searching all our equipment and clothing, and would take any of. our personal belongings they desired. Watches, rings, and other objects were taken by Fahnert, American Kits, ~, Schmidt, and some of the other German NCI’s. Many times were kicked, slapped, and hit with rifle butts on their backs and buttocks. One prisoner had from fifty to sixty punctures on his back and buttocks which had been made by German bayonets wielded by guards. For about six weeks, the only food we had to eat was a little dried sauerkraut and a little bread. When the Red Cross parcels for the prisoners arrived, they were taken by the Germans. The Germans ate the best of the food while we were on extremely short rations and almost allowed to starve. Walther Pickhardt was personally responsible for these conditions as he allowed them to go on. His excuse was that these measures were taken to prevent any prisoners from escaping from Stalag Luft #4. When we left Stalag Luft #6 for Stalag Luft #4., Walther Pickhardt was in command with Reinhard Fahnert as his second in command. From the railroad station at Keifeide, to Stalag Luft #4 a distance of about four miles, we were forced to run the entire way with our packs on 'our backs. Walther Pickhardt was in command of this operation, and I heard him give such commands as, "Let these American airmen have it".. calling us "Pigs" and "schweinhundes" and other disagreeable names. He gave his subordinates orders to double-time us and forced us to run the entire distance of four miles. When a man fell down exhausted, a German soldier would jab his bayonet into the man's body until he got up. Reinhard Fahnert was equally responsible for this outrage. At Stalag Luft #4, it was the German policy to shoot immediately, any prisoner caught trying to escape. Aribert Bombach, the camp commandant, condoned the activities of Fahnert and Pickhardt and was fully aware of what was going on at the camp. His answer was that this was done to prevent any man from escaping. At Stalag Luft #4, I secured a German uniform from a German soldier named. I put this German uniform on and walked through the front gates. I showed my faked pass and requested my German Army soldbuch. I then walked right pass the guards, proving that we could escape from this camp, if we wanted to. I did this just a few days before Christmas in December 1944. Ariber Bombach was surprised to see me outside the camp and called to his security officer, Walther Pickhardt, and said, "This is proof that a man can get out". He told Pickhardt that they would have to revise the security system of the camps. Pickhardt kept quiet and did not say anything at the time.

The Death March In honor of National POW Day—April 9—VFW presents the virtually unknown story of the American airmen who, in 1945, marched 600 miles in 86 days during one of the cruelist winters on record. Say the phrase "death march," and most Americans respond with a single word: Bataan. When Japanese troops overran the Philippines in 1942, they forced thousands of GIs and Filipino soldiers to march across 60 miles of the Bataan Peninsula in tropical heat with little or no food and water. Hundreds of Americans and thousands of Filipinos died in the five-10 day trek that came to be called the Bataan Death March, one of the greatest atrocities ever perpetrated against American fighting men. But there was another death march inflicted upon American POWs during World War II—a journey that stretched hundreds of miles and lasted nearly three months. It was an odyssey undertaken in the heart of a terrible German winter fraught with sickness, death and cruelty. Though experienced by thousands of GIs, it was all but forgotten by their countrymen. STALAG IN POLAND By early 1945, the war was going badly for the Germans, with Allied forces poised to overrun Hitler's homeland. As the Russian army approached from the east, the Germans decided to move the occupants of certain POW camps, called stalags, farther west.

Every American POW who experienced this evacuation has his own unique tale of misery, but none is more gripping than the incredible death march made by the men of Stalag Luft IV. ("Luft" means "air" in German, and it designated a camp holding mostly Allied airmen.) Stalag Luft IV -- in eastern Prussia, part of what is now Poland—held an estimated 9,000-10,000 POWs. The food was lousy, but it did exist, and the Red Cross parcels that arrived with some regularity contained enough additional nourishment to keep most of the men fairly healthy. Soap was abundant. The prisoners, almost exclusively NCOs and other enlisted personnel (including some Canadian and British airmen), were not made to work. Some medical care was available. Clothing was adequate. "Life in the camp was at least tolerable," recalls former POW Joe O'Donnell. "Compared to the march, it was a snap." In late January, the Stalag Luft IV airmen could see the distant flash of artillery fire, which meant an advancing front—and probably their liberation—were not far away. Then came the evacuation order and the departure of sick and wounded prisoners by train. More men went by rail a few days later. Finally, on Feb. 6, the remaining POWs set out on foot. No one knows for sure, but they probably numbered about 6,000. GIs were given access to stored Red Cross parcels, a tremendous windfall of food and other essentials, and many men started out bearing heavy loads. After a few miles, however, the roadside became littered with items too heavy -- or seemingly too unimportant—to carry. After all, their captors had told them the march would last only three days. German guards divided the POWs into groups of 250 to 300, not all of which traveled the same route or at the same pace. The result was a diverging, converging living river of men that flowed slowly but predictably west and [later] south. During the day, the prisoners marched four or five abreast, and at night were herded into nearby barns. With luck, a bed consisted of straw on a barn floor. Sometimes, however, the Germans withheld clean straw, saying the men would contaminate it and make it unfit for livestock use. On occasion, so many men crowded into a barn that some had to sleep standing up. And if no barn was available, they bivouacked in a field or forest. EATING RAW RATS Water (often contaminated) was generally available, but the Germans provided little food. GIs usually scrounged their own meals—and the firewood to cook them—often finding no more than a potato or kohlrabi to boil. On the irregular occasions when Red Cross parcels arrived, the GIs traded cigarettes and other items to guards and civilians for delicacies like eggs and milk. Some men resorted to stealing from pigs the feed that had been thrown to them and to grazing like cows on roadside grass. A handful of stolen grain, eaten while marching, provided many a mid-day meal. The acquisition of a chicken generated great excitement, but the little meat available more likely came from a farmer's cat or dog. T.D. Cooke tells of appropriating a goose and a rabbit from one farm: "We couldn't cook either one for about three days, and then we could only get it warm, but we ate both right down to the bones—then we ate the bones." Some men were even driven to eat uncooked rats. Physician Leslie Caplan, one of the few officers on the trek, later calculated that the rations provided by the Germans provided 770 mostly carbohydrate calories daily, and Red Cross parcels, when they were available, added perhaps 500-600 more. Troops often marched all day with little or no mid-day food, water or rest. Adding to the misery was one of Germany's coldest winters ever. Snow piled knee-deep at times, and temperatures plunged well below zero. Under these conditions, virtually all the marchers grew gaunt and weak. Virtually every POW became infected with lice. On sunny days, the men stripped to the waist and took turns removing the tiny livestock from one another. "I had no stethoscope," Caplan later wrote, "so [to examine someone] I would kneel by the patient, expose his chest, scrape off the lice, then place my ear directly on his chest and listen." RAMPANT DYSENTERY Diseases -- pneumonia, diphtheria, pellagra, typhus, trench foot, tuberculosis and others—ran rampant, but the most ubiquitous medical problem was dysentery, often acquired by drinking contaminated water. "Some men drank from ditches that others had used as latrines," recalled Caplan. Dysentery made bowel movements frequent, bloody and uncontrollable. Men were often forced to sleep on ground covered with the feces of those who passed before them. Desperate for relief, they chewed on charcoal embers from the evening cooking fires. Some men welcomed the frequent foodless days because it made the dysentery less severe. Blisters, abscesses and frostbite also became epidemic. Injuries often turned gangrenous. Medical care remained essentially nonexistent. "As a medical experience, the march was nightmarish," Caplan wrote. "Our sanitation approached medieval standards, and the inevitable result was disease, suffering and death." The Germans sometimes provided a wagon for the sick, but there was never enough room. When a GI collapsed and could not march, he was put on the wagon and the least-sick rider had to get off. Severely ill GIs were sometimes delivered to hospitals passed en route—and usually never seen again. Straggling marchers were sometimes escorted by guards into the woods and executed. "Often, there was a shot, and the German guard came back to the formation alone," recalls Karl Haeuser. Throughout the ordeal, marchers hung together, helping each other. They quickly developed a buddy system in which two to four men ate and slept together and looked out for one another. Many survivors credit their combine (as these groups were called) with saving their lives. When the Germans produced a wagon for carrying the sick but no horse to pull it, weary GIs stepped into the yokes. At night, aching and tired men carried their dysenteric comrades to the latrine. "Even beyond our combine buddy system, everyone tried to help everyone else," says O'Donnell. The death march was not without its lighter moments, however. John Kempf tells of two POWs who ran, against a guard's wishes, to the bottom of a muddy slope to grab a choice piece of firewood. In pursuing them, the irate guard slipped and jammed his rifle barrel into the mud—just before the weapon discharged, splitting the barrel wide open. On another occasion, POW Clair Miller traded a chocolate bar from a Red Cross package to a German woman for two loaves of bread. She probably had no way of translating the label on the chocolate that read Ex-Lax. BLACK COMEDY Day after torturous day, the shoe leather express continued. In late March, weary GIs arrived at their supposed destination, two stalags near Fallingbostel in north-central Germany. The camp's sights and smells—of food and smoke from warm stoves—set up this bizarre situation: POWs inside the camps wanted to get out, and the weary, starving men from Stalag Luft IV wanted desperately to get in. And for a time, they did, with some of the men taking their first shower in nearly two months as part of a delousing regimen. But these camps were already crowded, and there were no quarters for the marchers. Permanent residents received regular meals, but transients were forced to fend for themselves, much as they had done on the road. O'Donnell recalls following a Russian prisoner around, picking up the discarded kohlrabi skins the man threw to the ground. After only about a week, even this respite ended. With British and American troops approaching, guards mustered the men from Stalag Luft IV out of the camp (which was liberated a few days later) and set them to marching again. Incredibly, they doubled back on their earlier route, covering many miles a second time. For several more weeks, the great march continued as a kind of black comedy that saw the weary GIs herded first in one direction, then another, depending on the position of advancing Allied forces. FINALLY FREEDOM Eventually, however, the long-awaited liberation came—in various ways. Some GIs escaped and hid out until they could find an Allied unit. Three such airmen even stole a twin-engine plane and flew to France. One POW appropriated a farmer's horse and rode toward approaching U.S. forces -- with the steed's irate owner not far behind. Other GIs had the relative misfortune to be "liberated" by the Russians, which sometimes meant additional days of confinement at Soviet hands. Most of the POWs, however, simply marched into the glorious presence of American or British forces. Although these GIs had anticipated deliverance, their bliss was without bounds. "We were elated beyond words," says O'Donnell. "It was a tremendous joy." Finally, in spring 1945, the hideous march was over. From beginning to end it spanned 86 days and an estimated 600 miles. Many survivors went from 150 pounds or so to perhaps 90 and suffered injuries and illnesses that plagued them their entire lives. Worst of all, several hundred American soldiers (possibly as many as 1,300) died on this pointless pilgrimage to nowhere. The overall measure of misery remains incalculable. Though often overlooked by history, the death march across Germany ranks as one of the most outrageous cruelties ever committed against American fighting men. Fittingly, a memorial to these soldiers now stands on the Polish ground where Stalag Luft IV once stood. Editor's Note: Joe O'Donnell, a vet of the German death march and consultant for "Death March Across Germany", has compiled and self-published five volumes about Stalag Luft IV and the death march. For information, contact O'Donnell at . Also, thank you to Karl Haeuser of Cayucos, Calif., for bringing this long neglected story to our attention.

Much has been made of and written about the forced marches, and I can only report on what happened to me and those around me, and on what I have learned as a result of a great amount of follow-up research and conversations. Some of my comments here will be on events and conditions much reported on before, and I make them knowing some of them will not please those who have written difficult-to-believe accounts of their and others experiences on similar, but much shorter duration marches. This movement of allied prisoners across Germany and occupied areas taken by a great number of small groups and lasting various lengths of time has been called The Death March, or the Black, or Bread March. I have read accounts of hundreds of Americans that died around the writer, and feel that if all the numbers of the dead in the accounts of the event that have been published in the Ex-POW Bulletin during its history were combined, one would end up with a total of many thousands. Actually, of the over 90,000 of us known to have been held by the Germans, a total of 1,121 are positively known to have died while in captivity. Balancing this small death rate is the statistical probability that if that number of us held there had not been captured, but continued in combat, even with the number of missions limiting such time for flyers, a larger number of us would no doubt have been killed. Of those almost 8,000 of us who started at Luft IV, only 6 are absolutely known to have died on the march. None died in the group I was in, and although it occasionally changed members when one overtook another, I never heard anyone mention anyone's death. To call my group's walk across Germany guarded by non-hostile members of, first the Luftwaffe, and finally the Volkstrum a Death March, denigrates the terrible ordeal of those POWs who endured the Bataan Death March in the Pacific. The distances walked certainly varied by groups and the length of time they walked, and no portion of the experience has been more argued or exaggerated. I have read reports that claimed the writer had walked as much as a thousand miles. Cecil Brown, my closest companion on the walk kept notes of each of our 57 days of walking and the distances covered. His calculations were based on the roadside kilometer markers we passed, plus some estimates when none were present. His result is 931 kilometers, or 580 miles. Several years ago, using 1/50,000 scale maps of the area (46 sheets required) and tracing our route over them with a precise cartographic instrument, I arrived at 470 miles. I will settle for the difference, 525 miles, as being a reasonable estimate. The shortest one-day distance was 5 kilometers and the longest 30. The latter was while we skirted the German rocket testing area at Pennemuende on the Baltic coast. Before we began our walk, we knew the end for both Germany and our time as prisoners was not far off. A clandestine radio somewhere in the camp furnished us daily news from BBC, so we knew how the fronts in the west and east were moving. If the radio was taken on the march, it was not with my group, and even if it had been, the lack of accessible power sources would have almost negated its usability. So while on the road our morale and expectations were kept up by things like: the movement of civilians west and German troops east; questions to the guards that would frequently get answers like "Ask Eisenhower, he will be here soon"; and in the last few weeks, the large amount of unopposed American and British air action. As a result, our morale and spirits remained much higher than they could have possibly been had the event taken place before the invasion of the continent. I think a sense of relief and even a sort of elation overcame our fear that anything other than our liberation could finally happen. As noted, we were far from the only groups on the roads. Often we were paralleling or even mixed in with German civilians, elderly people, women and children fleeing west ahead of the advancing Soviet troops. They were walking, and pushing or pulling carts and wagons containing the only possessions they had; frequently old people and infants were also on the wagons. One afternoon, I pushed a woman's pram with an infant in it. Her possessions were in the pram, or tied to it, and she was carrying a child that would periodically walk for maybe a quarter of a mile before having to be picked up and carried again. We POWs had no idea of the existence of the concentration camps, so the plight of this woman and her children brought home to me the downside of war more than any single thing I had encountered previously. I have often thought about her and the children since them, and wondered about their fates. As to general

conditions for us on the march that I feel pertain to any group starting

at Stalag Luft IV: The weather and the temperatures greatly affected us until April. It has been called the coldest winter Germany had during the war, and with us inadequately clothed and shod, it caused us problems. I have read and heard some extreme estimates of the low temperatures we encountered and the resultant cases of frostbitten feet. While I can't argue with the possibility of cold-induced medical conditions, I do question the temperatures that have been given as causing them. Food was absolutely inadequate. When liberated, many men were showing signs of edema to their extremities—an early symptom of starvation. And I have often wondered how much longer the move would have had to last before real starvation began to cause casualties. The food consisted of what the Germans accompanying and guarding us managed to acquire in quantity enough to amount to anything when distributed, and then it was generally limited to small rations of potatoes, a rare small portion of watery soup, bread and occasional varied items from Red Cross parcels. Brown's log shows we were given bread 29 times during the 86 days period. On three occasions, the issue was a loaf per man and the others ranged from as much as 1/4 to 1/15. When in the big tent, we were given approximately 12 oz. of very thin carrot soup daily. Mostly in bits and pieces, we each received the equivalent of six and one half Red Cross parcels during the entire period. We added to this by bartering scarce cigarettes and other Red Cross items with German civilians and foreign nationals working on farms, and by scrounging, thievery of vegetables stored in mounds in the fields and even foraging for edible wild plants. We went to sleep hungry, awoke that way and stayed that way during the day. Most conversations quickly evolved into talk about food, often including the impossibly large and varied contents of the meals we were going to eat when we got home, frequently even including the details of preparing each item. I feel I held my weight of about 160 lbs. while in the two Stalag Lufts. When I weighed myself after liberation and a couple of good meals of Army chow hat I managed to keep down, I hit 121. Had we remained in Luft IV with the routine and ration situations unchanged during those 86 days, we would have been given about the same amount of bread, more Red Cross food, and a greatly increased German ration. And except for two roll calls a day, one could be (and some were) a complete bed potato and bum up many, many fewer calories. If our long walk required a name, one might be tempted to title it the "Misery Walk" and not be wrong. If feel however—and remember this story addresses things as I sag; and currently see them -- that the absolute knowledge that the big end was very near tempered the misery, hunger and even the uncertainties about the period between any current time and the end. Liberation! As noted earlier, it finally came when we were surrendered to our forces. Knowing it was getting closer each day was probably the main thing that sustained us during our almost three-month-long migration. Just the word itself denotes freedom, but it must be long and hopefully awaited, anticipated and then finally realized for it to have its full, almost indescribable meaning. Liberation. The good guys came and took you away from the bad guys! Your country had the will and its military had the initiative, the guts and the ability to kick butt and win! To get you and all the marbles. The events above took place almost fifty-five years ago. Following them and a short break from the military, I re-enlisted, and for three years was a crew member on B-36's, B-29's and B-50's. From that I switched to a new career in the Air Force devoted to training in survival, evasion and escape, and coping with captivity. In this capacity, I attended many training programs, worked with thousands of flying personnel and climbed mountains, traveled on glaciers, rafted and paddled on rivers, hunted and fished, built and lived in igloos on Arctic Sea ice, trekked many hundreds off miles through forests in many parts of the world, attended interrogation schools in two countries and played interrogator as well as POW in many US military and NATO training exercises worldwide. I even spent four more years in Germany. Today, I look back on all of it, including captivity, as one great adventure and learning experience. The enjoyment I find in looking back is tempered however by the knowledge that many who have been POWs never lived to either look back on it, or enjoy subsequent experiences. "Part 1 Capture and the Camps" available upon request from Greg Hatton Lest We Forget During the winter of 1944-45, 6,000 Air Force noncoms took part in an event of mass heroism that has been neglected by history. Most Americans know, in at least a general way, about the Bataan Death March that took place in the Philippines during April 1942. Few have even heard of an equally grim march of Allied POWs in northern Germany, during the winter of 1945, (the most severe winter Europe had suffered in many years). The march started at Stalag Luft IV in German Pomerania (now part of Poland), a POW camp for US and British aircrew men. Early in 1945, as the Soviet forces continued to advance after their breakout at Leningrad, the Germans decided to evacuate Stalag Luft IV. Some 1500 of the POWs, who were not physically able to walk, were sent by train to Stalag Luft I… On Feb. 6, with little notice, more than 6,000 US and British airmen began a forced march to the west in subzero weather, for which they were not adequately clothed or shod. Conditions on the march were shocking. There was a total lack of sanitary facilities. Coupled with that was a completely inadequate diet of about 700 calories per day, contrasted to the 3,500 provided by the US military services. Red Cross food parcels added additional calories when and if the Germans decided to distribute them. As a result of the unsanitary conditions and a near starvation diet, disease became rampant; typhus fever spread by body lice, dysentery that was suffered in some degree by everyone, pneumonia, diphtheria, pellagra, and other diseases. A major problem was frostbite that in many cases resulted in the amputation of extremities. At night, the men slept on frozen ground or, where available, in barns or any other shelter that could be found. The five Allied doctors on the march were provided almost no medicines or help by the Germans. Those doctors, and a British chaplain, stood high in the ranks of the many heroes of the march. After walking all day with frequent pauses to care for stragglers, they spent the night caring for the ill, then marched again the next day. When no medication was available, their encouragement and good humor helped many a man who was on the verge of giving up. Acts of heroism were virtually universal. The stronger helped the weaker. Those fortunate enough to have a coat shared it with others. Sometimes the Germans provided farm wagons for those unable to walk. There seldom were horses available, so teams of POWs pulled the wagons through the snow. Captain (Dr.) Caplan, in his testimony to the War Crimes Commission, described it as "a domain of heroes." The range of talents and experience among the men was almost unlimited. Those with medical experience helped the doctors. Others proved to be talented traders, swapping the contents of Red Cross parcels with local civilians for eggs and other food. The price for being caught at this was instant death on both sides of the deal. A few less Nazified guards could be bribed with cigarettes to round up small amounts of local food. In a few instances, when Allied air attacks killed a cow or horse in the fields, the animal was butchered expertly to supplement the meager rations. In every way possible, the men took care of each other in an almost universal display of compassion. Accounts of personal heroism are legion. Because of war damage, the inadequacy of the roads, and the flow of battle, not all the POWs followed the same route west. It became a meandering passage over the northern part of Germany. As winter drew to a close, suffering from the cold abated. When the sound of Allied artillery grew closer, the German guards were less harsh in their treatment of POWs. The march finally came to an end when the main element of the column encountered Allied forces east of Hamburg on May 2, 1945. They had covered more than 600 miles in 87 never-to-be-forgotten days. Of those who started on the march, about 1,500 perished from disease, starvation, or at the hands of German guards while attempting to escape. In terms of percentage of mortality, it came very close to the Bataan Death March. The heroism of these men stands as a legacy to Air Force crewmen and deserves to be recognized. In 1992, the American survivors of the march funded and dedicated a memorial at the former site of Stalag Luft IV in Poland, the starting place of a march that is an important part of Air Force history. It should be widely recognized and its many heroes honored for their valor. Chris Christiansen, Protecting Powers delegate (from his book: Seven Years Among Prisoners of War; Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 1994) As early as March 1944, the camp commandants' had received instructions that in case of imminent invasion all POWs were to be evacuated from the border areas and the invasion zones. From September 1944 onward this evacuation claimed an incredible number of victims, and the closer the Allied armed forces came to the German borders, the more chaotic and undisciplined was the evacuation. I do not know just how many Allied POWS were killed in the process, but the number of British and Americans alone might be an indication: during the period from September 1944 through January 1945, the evacuations had claimed 1,987 victims, but during the last three months of the war that number increased to a total of 8,348. With so many dead among those who were relatively well treated and who-much more importantly, received Red Cross parcels with food for their daily meals, it can be assumed that the number of dead among the Russian POWs must have been considerably higher. About one hundred thousand POWs from the camps in Silesia were evacuated and marched through Saxony to Bavaria and Austria. Transportation by train had been planned, but had proved impossible because of the rapid Russian advance. Lack of winter clothes, food and quarters claimed many victims. Over-excited party members and nervous home guard (members of the "Volkssturm") decided the fate of the POWs in these last weeks of the war. The German High Command wanted to keep the POWs at any cost, to be able to negotiate more favorable peace terms, and it was therefore necessary to evacuate them under these most inhumane conditions instead of just leaving them to await the advancing Allied armies. "Testimony of

Dr. Leslie Caplan FOR THE WAR CRIMES

OFFICE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Perpetuation of

Testimony of Dr. Leslie Caplan (Formerly Major, MC, ASN 0-41343) Questions: Q.

State your name, permanent home address, and occupation. Q.

State the date and place of your birth and of what country you are a

citizen. Q.

State briefly your medical education and experience. Q.

What is your marital status? Q.

On what date did you return from overseas? Q.

Were you a prisoner of war? Q.

At what places were you held and state the approximate dates? Q.

What unit were you with when captured? Q.

State what you know concerning the mistreatment of American prisoners of

war at Stalag Luft #4. Q.

Were these wounds serious enough to cause any deaths? Q.

Did you see these men at the time of the bayoneting? Q.

Did you see any of the men who were bitten by dogs? Q.

Do you know how many men were injured as a result of the bayonet runs? Q.

Who told you of these incidents? Francis A. Troy, Box 233, Edgerton, Wyoming, the other enlisted man, and "American Man of Confidence" should also verify the incidents. Both of these enlisted men were also on the forced march when Stalag Luft #4 was evacuated. Q.

Do you know if the Commandant was responsible for the bayoneting and dog

bites? Q.

For what reason was "Big Stoop" disliked? Q.

Could you give any specific incidents of such mistreatment by "Big

Stoop"? Q.

Can you describe "Big Stoop"? Q.

When you arrived at Stalag #4, were you subjected to the bayonet runs? Q.

Did you have any duties assigned to you while a prisoner? Q.

State what you know concerning the forced march from Stalag Luft #4? Q.

Who was in charge of this march? Q.

How much distance was covered in this march? Q.

How much food was issued to the men on this march? The area we marched through was rural and there were no food shortages there. We all felt that the German officers in our column could have obtained more supplies for us. They contended that the food we saw was needed elsewhere. They further contended that the reason we received so little Red Cross supplies was that the Allied Air Force (of which we were "Gangster members) had disrupted the German transportation that carried Red Cross supplies. This argument was disproved later when we continued our march under the jurisdiction of another prison camp; namely Stalag #IIB. This was during the last month of the war when German transportation was at its worst. Even so, we received a good ration of potatoes almost daily and received frequent issues of Red Cross, far more than we were given under the jurisdiction of Stalag Luft #4. Q.

What sort of shelter was provided during the 53 day march? Q.

What were the conditions on this march as regards drinking water? Q.

What medical facilities were available on the march from Stalag Luft #4? Q.

What medical supplies were issued to you by the Germans on the march from

Stalag Luft #4? Q.

To your knowledge, did any sick man die as a result of neglect by the

Germans on the march from Stalag Luft #4? NAME

It is likely that there were other deaths that I do not know about. Q.

Did all these deaths occur while the men were directly under the control

of Stalag Luft #4? Q.

What were the circumstances which led to the deaths of these men? Q.

What other mistreatment did you suffer on the march from Stalag Luft 4? Q.

Was the suffering that resulted from the evacuation march from Stalag Luft

4 avoidable? On 30 March 1945 we left the jurisdiction of Stalag Luft 4 when we arrived at Stalag Luft On 6 April 1945 we again went on a forced march under the jurisdiction of Stalag 11B. Our first march had been in a general westerly direction for the Germans were then running from the Russians. The second march was in a general easterly direction for the Germans were running from the American and British forces. Because of this, during the march under the jurisdiction of Stalag 11B we doubled back and covered a good bit of the same territory we just come over a month before. We doubled back for over 200 kilometers and it took 26 days before British forces liberated us. During those 26 days we were accorded much better treatment. We received a ration of potatoes daily besides other food including horse meat. We always barns to sleep in although the weather was much milder than when we had previously cover this same territory. During these 26 days we received about 1235 calories daily from the Germans and an additional 1500 calories daily from the Red Cross for a total caloric intake. I believe that if the officers of Stalag Luft 4 had made an effort they too could have secured us as much rations and shelter. Q.

To what officers from Stalag Luft 4 did you complain? Q.

Can you describe Capt. Weinert? Q.

Are there any other incidents that should be reported. Q.

Do you have anything further to add? (signed) Subscribed and sworn to before me, this 5 day of January 1948. (signed) CERTIFICATE I, William C. Hoffman, Lt. Col. Certify that Dr. Leslie Caplan personally appeared before me on December 31, 1947 and testified concerning war crimes; and that the foregoing is an accurate transcription of the answers given by him to the several questions set forth.

|

![]()

RETURN TO HEROES OF CAMDEN, NEW JERSEY